Academy Awards offer distorted view of Hollywood life

On Sunday, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences will present its awards for the year’s “best” cinematic achievements. The Academy Awards is a celebration of success. It’s well worth remembering that for most who live in Hollywood, such success is elusive, and the Academy Awards ceremony offers a distorted view of life in the shadow of the dream factory. The following expose is an unflinching and thought-provoking look at the all-too typical of the experiences of Hollywood denizens.

In a rundown bachelor apartment in Hollywood, there lives a dream. A dream denied and battered, scraping by on memories of might-have-been, at that cold intersection of Loneliness and Possibility, but actually closer to Yucca and Las Palmas, literally speaking. For $750 a month, one man who is the living embodiment of Hollywood watches from his window as the traffic, which is a metaphor for the world at large, passes by.

“They’re heading to Chateau Marmont,” he says, knowingly. His voice is gravelly, with the age that comes from wisdom, of having seen and experienced much in pursuit of that elusive dream of Hollywood fulfillment.

I ask him how he knows this, and he replies, “Because it’s where I’d go, if I had any hope.”

His name is Heiney Spitstarsky, I think. That is what it sounds like he calls himself. He becomes severely agitated when asked to repeat himself. 40 minutes before, I first met Mr. Spitstarsky at a Laundromat on Cahuenga. I was doing a load of whites; hot wash, cold rinse. Mr. Spitstarksy came in wearing a shabby LA Dodgers baseball cap (just what is he “dodging”? certainly not life, that’s for certain) a stained polo shirt with a Ralphs logo, tattered jeans and sneakers that were at least five years old, and worn through in places, leaving visible the leathery skin of his feet.

As he approached me, his pungent odor announced him, and I took my eyes from the book I was reading. The Day of the Locust, if you must know.

“I needa use your hot water,” he said. Without waiting for a reply, he opened the top of the washing machine and placed under the stream of hot water that was splashing over my clothes a styrofoam container of ramen noodles. “I ain’t eat yet today,” he explained.

In these days of recession, when everyone is finding ways to save money, I can’t help but admire the man’s initiative. It will be the first of many frugalities he would teach me.

“Have you met Cameron Diaz?” he asks, earnestly.

I admit I have not.

“I see her around sometimes. Down at the Chinese for premieres. Sometimes she’s at Runyon Canyon. I just thought you might know her. Are you interested in movies?”

Isn’t everyone?

“I’ve worked in movies,” he says, using a dirty plastic fork to pull noodles out of the now-steaming container. “It’s been awhile, but I been working in movies in the ‘70’s. You let me tell you all about it, okay, but later. Do you have a quarter for the bathroom?”

I explain to him that I only have exactly enough quarters to do my laundry, and he slams his fist against the washing machine, in a display of histrionics that would make any Hollywood citizen proud. His small eyes widen startlingly, his nostrils flare. He points a dirty finger at me and intones dramatically, “Fine. But I’m gonna tell you about my life in movies when your laundry is done.” I note that his fingernail appears to be bleeding.

Slurping the last of his noodles, the man steps out of the Laundromat and lays down on the sidewalk, unzips his pants, and begins to masturbate. It is a performance worthy of the most seasoned Hollywood performer and yet, ironically, any pedestrians who happen by ignore him.

That in itself is a metaphor.

All of my friends have real jobs, and none of them can come pick me up. I even call my ex-girlfriend to check with her. I go so far as to promise to perform cunnilingus on her if she’d drive me home. But no. “Call the police, if you’re so worried,” she says. But the police won’t come unless I’m in imminent danger.

Unfortunately, I walked to the Laundromat today. I briefly consider leaving my clothes and rushing back home before Heiney can return. No doubt I am fearful because I see in him a reflection of my own possible failures in this town known as Tinsel, and this business called Show. That, and I am pretty sure he is capable of murder. The way Hollywood murders dreams.

Heiney sits on the sidewalk, watching the Laundromat. His eyes are on me, and when I look up from the book, he smiles big and wide, the skin of his face cracking like distressed naugahyde and he uses two fingers to point at his eyes, then at me. He is waiting, determined to be heard.

“I will follow you home,” he says, as I sling my bag of clothes over my shoulder. “You gotta hear about this!”

“Uh, why don’t we just go to your place, and then I’ll go home from there.” He isn’t going to leave me alone unless I listen to his story. He demands to be heard, after so many years of suffering through the Hollywood system.

Along the way back to his place, he stoops to pick up cigarette butts. “There aren’t as many of these as there used to be, now that smoking is practically illegal.” But there is little time for us to ponder the tragedy of unintended consequences, for he stops at a trash bin to retrieve a Jack-in-the-Box beverage cup. With his bleeding finger he points at the cup and says, “Free refills at Jack-in-the-Box. I don’t know why anybody would throw away one of these cups!”

Clearly, Heiney is a frugal man. His bachelor apartment provides ample evidence of this – his furnishings were all scavenged from street corners and dumpsters. The floors are littered with items never to be thrown away; old books, magazines, papers. He places the newly found Jack-in-the-Box cup on a stack of at least 20 others, and places the cigarette butts in a box beside his futon.

I am admonished to take a seat and I do, upon a fraying ottoman. “This is a great place,” I tell him.

“Worker’s comp,” he says, nodding his head, his lip curled in a snarl. I assume he is telling me how he is able to afford the place, but I am reluctant to ask him to elaborate.

“Great location,” I add. Right in the heart of the Hollywood dream factory. It is both ironic and appropriate that, during certain times of the day, the shadow cast by the Kodak Theater, in which is held the annual Academy Awards, falls directly over the building. Also, a billboard advertising jeans aimed at young people.

“That sign makes no sense,” he tells me. “If it’s for jeans, then how come that woman’s butt is naked?”

I admit I don’t know. “Let me see your wallet,” he says.

Uneasily, I ask him why.

“I want to see if you’ve got any money in your wallet.” He is standing before me, his entire body trembling, his fists clenched, knuckles white. He shouts obscenities and tells me that he will do to me what Hollywood has done to him if I don’t comply. He says this in so many words. I oblige him.

“I thought you only had enough money to do your laundry, you lying bastard,” he says, snatching the $18 in cash from my wallet. He is right; Hollywood is a dishonest place. “This is how much it’s going to cost you for an interview with me.”

“I got to Hollywood in 1965,” he tells me, taking a long drag on his plantain. “The very day I got here I ran into this guy at Musso and Frank’s. He was working on the script for a movie called ‘Don Juan of Hoboken,’ which was to star Paul Donat. I think maybe Van Johnson ended up in it.

“I told him, this guy, I’d do anything to break into pictures, and he told me he’d introduce me around if I’d fellate him. That means give him a BJ, in case you didn’t know.”

I tell him I know what that means.

“They call it a hummer now, too. Maybe that’s what you know it as. Suck him off, is what he asked me to do. So I did. He was a good writer anyway and he introduced me to the head no pun intended of Colossal Pictures. Actually, it turned out it was one of this guy’s bookies. This guy owed his bookie a lot of money, and I sort of helped him pay off some of his debt by giving this guy a hummer, too. Of course, at the time I thought I was servicing the head of a movie studio.

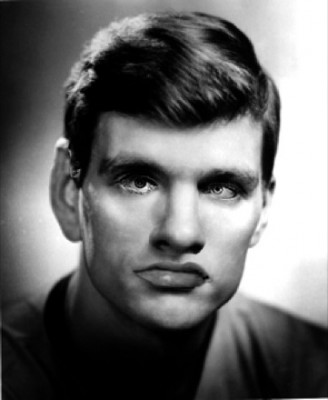

“I was a good-looking guy back then, too. Here’s a headshot I took in 1968, if you don’t believe me.” He hands me his headshot, and tells me to keep it. He has plenty more, and maybe I know someone who can give him some acting work, he says, poignantly.

Heiney’s story could have been told by any of the thousands of random people you meet every day on Hollywood Blvd at noon on Tuesday. It is the all-too-common tale of Hollywood expectation. “Anyway, he took me out to one of those Alfred guy’s parties. He was famous for them, you know, the chandelier and what not. Very notorious. Ball bats. Spinners.” Heiney makes a twirling motion with his fingers, and presses his tongue against the inside of his cheek. “Also, a lot of stuff with the crippled children; reverse shorty, they called it at the time. Everyone knew what was really going on, and people are still talking about it to this day! The Hollywood Hills howled – some of them even got into toileting, at least on the corners. I’m sure you heard about all of this stuff – it was notorious. Plaster relief.”

I nod my head. I have no idea what he’s talking about, but I sense the realness of his experience.

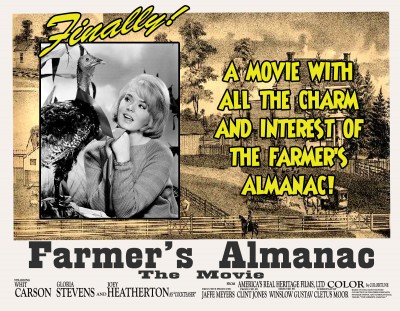

“You get a lot of information out of scenarios like this. That was where I met Orchard Greene. I don’t know why, but I impressed him, and he hired me to be his assistant on ‘Farmer’s Almanac: The Movie.’

“Orchard worked the craft services on that picture. I believe that was Cooke Nelson’s first movie. I always thought he’d be a bigger star than he was, but he only made a few pictures.

“Anyway, after that I got hired on as an assistant runner at Careening Entertainment Resources. They contracted out with a lot of the smaller production companies, and I ended up doing some running on a bunch of B-type movies – “Trollop From Cleveland,” “Five Hats for Mr. Dunlap,” “The Rumpot and the Reprobate,” “Tenderly Melodramatic,” “The Tuba Master,” “My Third Wife,” “She Only Said Maybe,” “Embarrassing Soiree,” and “Bland Central Station.” You ever see any of those?”

There is eagerness in his eyes as he asks me the question. And there is tension in his hands, which he has balled into fists. I don’t have the heart to tell him I haven’t even heard of these films. So I lie. Just as I lied about the money in my wallet.

Hollywood is a town built on lies. Even that previous sentence is a lie, when you think about it. Everything circles round on itself.

Afraid to ask him exactly what an “assistant runner” does, I ask him if he ever rose above the rank of assistant runner. His eyes flash. “It was a combination of things, I guess. That was all in 1971, I believe. Then I lost that job when this kid attacked me in the parking lot. He didn’t so much attack me as look at me in a way that made me uncomfortable. He did this motion with his hand, sort of like this—” Heiney here makes a motion that looks to me like a wave “—and I got kinda freaked out; it had been a long weekend. Well, that kid was the son of a producer, or something, so I knew I was in trouble. I wasn’t going to go back to work, but when I got home to my apartment, there were some folks waiting for me. I couldn’t just go in and get my stuff, you know?”

I tell him I know.

“I did get a job as a crate packer and joistman on a movie called ‘A Thimbleful of Prune Juice,’ with Bill Shatner and Jo Anne Worley; that was in 1975, I believe. Should have been my big breakthrough, but that movie barely even had a release. I think it played at a few drive-in theaters in Arkansas, or something. Carter kept it out of Georgia.”

I ask him what he did between 1971 and 1975, and Heiney stares off into the distance, as if scanning the years. “I think I met Evel Knievel once,” he says, absently. “I loaned him five dollars to get a malted and fries.”

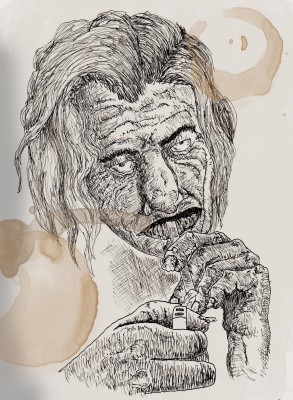

On the floor to my left I spot an intricate line drawing, and pick up the dirty piece of paper. “Is this you?” I ask. The image bears a striking resemblance to my host.

He tells me that it is a self-portrait. He says the title of the picture is “Me With a Crack Pipe,” but I believe a more appropriate title is “Typical Hollywood Reality.” Graciously, Heiney agrees to let me take it home. “I got about a thousand drawings of myself.

“Also, I wrote a screenplay. Since you liked my drawing so much, you should read it,” he tells me.

Because it’s clearly intended as an order, I nod my head. “I’d love to take a copy home with me and give it a look,” I say.

He shakes his head. “Not take home,” he says. “There’s only one copy.” After several minutes of digging through the bottom of a creaking, decrepit armoire, he presents me with a large volume bound with red yarn. I estimate its length to be at least 500 pages; many of them brittle and yellowed with age. He places the pages on my lap.

“Read,” he says. “I’m eager to get your opinion.”

Before I can reach down to the manuscript I hear the growling of an animal. The sound is coming from under the fraying couch on the other side of the room. “That’s just Peeve,” he says. As if in answer to my confused look he adds, “Peeve is my poodle. Forget him – if he likes you he’ll come out. Just read.”

The pages are a hodgepodge of typed and handwritten notes, some of them in crayon, that bear a superficial resemblance to a screenplay. The story is a long and meandering one about an old, drug addicted man who dies and awakens in heaven in the body of a 16 year-old girl. The girl stands before a panel of judges, one of which is a ditzy former pop singer, another is an approachable, positive, overweight black man who employs heavy use of street vernacular, and the last is an angry, acerbic British man. She is then instructed to relay the details of her life, which she does, in brutal, boring detail, including lingering descriptions of sexual escapades with the actress Cameron Diaz.

The pages weren’t numbered, but my estimate of 500 wasn’t far off.

Interspersed among the “screenplay” pages are pieces of construction paper, on which Heiney has pasted photos of the actress Cameron Diaz. Some of these photos are surrounded by crudely drawn hearts. Some of them have Heiney’s head superimposed on the body of the male companion in the photo with Ms. Diaz. Toward the end of the manuscript, Heiney has placed a photo of his own head on Ms. Diaz’s body, under which he had scrawled the words, “Better head for her.” It is doubtless a commentary on the way in which the Hollywood dream factory mutilates anyone who works within it.

Finally, after several hours, I finish reading. “It’s better than the screenplay to ‘The Social Network,’” I tell him, truthfully. “I’ve never read anything that more accurately conveys the experience of living in Hollywood.”

“You didn’t even look at the back page!” he says, angrily.

I turn the volume over and see written there in a shaky hand, “MY ACCEPTANCE SPEECH.” It is apparently a speech to be delivered by Heiney, should he win the Academy Award. I cannot remember it verbatim, but the gist of it was, “I wish to dedicate this award not to the wonderful cast and crew of this film, but to all the dreamers in Hollywood, who never give up on their dreams, and keep going until they make their dreams come true.”

“It’s so perfect, it’s scary,” I tell him. Earlier in this essay I described Heiney Spitstarsky as the living embodiment of Hollywood. Or I implied that he was the living embodiment of Hollywood. I might go back and make it more explicit. Anyway, that’s only partially true. He is also the ultimate martyr-savior of this godless country. And, not to get too melodramatic, unless we listen to his siren song of misery, we are all doomed to live it ourselves.

Also, he needs about $50,000 to make his movie. I told him I’d help him set up a paypal account, so he would let me leave his apartment.

I’m afraid, however, that was just one more Hollywood lie.

Latest posts by Ricky Sprague (Posts)

- Meet the start-ups that are thriving in the current economic recovery - May 27, 2016

- How a Wonder Woman comic from 1942 led to the Great California Cow Exodus of 2012, maybe - November 28, 2012

- A common-sense approach to restoring economic prosperity - November 19, 2012

- New Philip K. Dick novel too absurd to be believed - September 17, 2012

- My 90 Days, 90 Reasons submission - September 12, 2012

Print This Post

Print This Post

Discussion Area - Leave a Comment