Alan Moore is right about “Before Watchmen,” alas

I. Look on the Watchmen, Ye Mighty

Back in February 2012, DC Comics officially announced that they would begin publishing seven miniseries based on characters and situations from what many people consider to be the greatest superhero graphic novel of all time, Watchmen. The series, which will begin shipping in June, are known collectively as “Before Watchmen,” which right there gives you a hint about the main problem with these books, and the mainstream comic book industry in general.

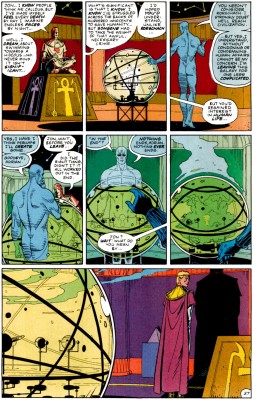

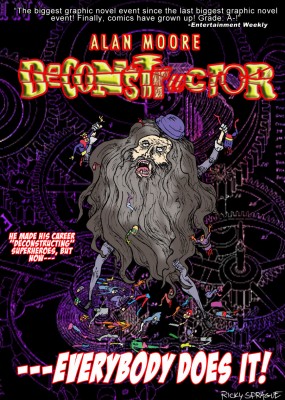

The writer of Watchmen, Alan Moore, is the most important and influential author of graphic fiction since Stan Lee. Watchmen is the most influential graphic novel of all time. Since its publication, it has been the benchmark by which all other works are measured. Most mainstream comics creators have been re-writing it for 25 years. It’s a masterpiece, at least in the Renaissance sense of that term. The three primary creators, Mr. Moore, illustrator Dave Gibbons, and colorist John Higgins, all employed every tool at their disposal in its composition. It was a unique experiment in storytelling and printing techniques, an elegantly constructed and dense meditation on the idea of supeheroism, and a deconstruction of the serial comic book form itself.

It is also ruinously flawed, self indulgent, and ultimately nonsensical. To begin with, there is that ending. As Grant Morrison noted in his book Supergods,

Ultimately, in order for Watchmen’s plot to ring true, we were required to entertain the belief that the world’s smartest man would do the world’s stupidest thing after thinking about it all his life.

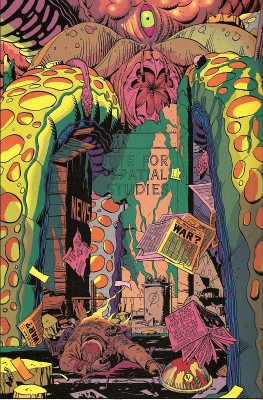

And Ozymandias’s plan is profoundly, monumentally stupid — to attempt to create a state of peace on earth by simulating a failed invasion by a giant alien Cthulu vagina, murdering millions of New Yorkers in the process.

The master plan was to teleport something that looks sort of like a giant Cthulu vagina into Manhattan and kill millions of people. Some plan.

But it’s not just that the plan is stupid, and not just that it wouldn’t work — and even at the time the issues were published, there was no reason to believe that it would. It’s also that the plan is vicious authoritarianism designed specifically to protect the existing power structure by sacrificing a few million civilians to save the politicians and bureaucrats who caused all of the problems in the first place. It apparently didn’t occur to Ozymandias to, for example, simply assassinate the leaders of the Soviet Union and the United States. By extension, this idea didn’t cross Mr. Moore’s mind, either — if it had, the story would have been a lot shorter. By killing Rorshach, the dispassionate and logical Dr. Manhattan gives his approval of the plan. The audience is meant to come to the same conclusion: That a few million innocents had to be slaughtered to “save the world.”

To use the language of the current “Occupy” movement, this is the type of hypothetical question that one One-percenter might ask another One-percenter: “How many of the ninety-nine percent would you be willing to kill to maintain the current power structure?” Kill too many, and there might not be enough left over to continue using for your nefarious purpose. Kill too few, and you haven’t made your point. There’s a balance, you see.

By abandoning the story where he does, Mr. Moore absolves himself of the responsibility to examine the ramifications of Ozymandias’s stupid, immoral plan. In 1987, when that final issue appeared, the ending felt ludicrous. One needed only to look at the war on drugs — a war declared by Richard Nixon, the president in Watchmen — to see that life for those who survived would be made all the more miserable. Now, 25 years on, the ending rings all the more false. We have real-world evidence that Ozymandias’s plan would have done nothing more than cement power for those who already had it. If you don’t believe me, then wave to the drones while you read the PATRIOT Act, and the NDAA, or try getting on an airplane without being “patted down.”

Mr. Moore compounds the problem by introducing two everyman characters in the form of a teenager reading a pirate-themed comic book called “Tales of the Black Freighter,” and the newsstand vendor from whom he (doesn’t) buy the comic. These two characters serve the function within the story of introducing the idea that in this world in which superheroes actually exist, superhero comics have fallen out of favor with the public. The Black Freighter story the teenager is reading is meant to be a metacommentary on aspects of Watchmen‘s primary plot. Alan Moore himself trespassed on the work by stating that The Black Freighter’s story is meant to reflect Ozymandias’s stupid decision:

Yeah, there’s even a bit where I think Adrian Veidt [Ozymandias] says at the end that he’s been “Troubled by dreams lately, of swimming towards – ” and then he says, “No, it doesn’t matter, it’s not important” and I mean it’s pretty obvious that he’s dreaming of swimming towards a great Black Freighter. Yeah, there’s a parallel there.

Oh, and when these two everymen are slaughtered, they’re meant to show the enormity of Ozymandias’s decision, by giving us a glimpse into the lives of two of his victims. So, Moore sees these characters as nothing more than a means to an end for him. They serve his narrative purpose, and for their trouble, they’re slaughtered. His attitude is a reflection of that of Ozymandias; a means to an end.

Rather than deal with the implications of Watchmen‘s cowardly, morally bankrupt ending, DC is choosing to create “new” stories that take place before the events of the book. As I’ve already written, mainstream comics have a history of scrupulously avoiding the real-world implications of their stories, but the whole point of Watchmen was, allegedly, that this would be the story of what would happen if superheroes really actually existed. That’s why everyone in that world reads pirate comics! Mr. Moore and Mr. Gibbons were interested enough in the world they were creating to speculate about the state of the comic book industry, but they didn’t have enough intellectual curiosity to think through the implications of Ozymandias’s plot.

Extending the story out from the dubious ending makes sense not only from a story and financial standpoint, but also from a moral one. But this “prequel” idea shows just how bankrupt the comic book industry has become — from a story, financial, and moral standpoint. In trying to justify the existence of these new miniseries, DC Comics co-publisher Jim Lee said,

“One of the key characteristics of the comic book medium is that it is not brought to life by just one voice. These universes are developed and evolved by multiple creative voices, over multiple generations. The influx of new stories is essential to keeping the universes relevant, current, and alive. Watchmen is a cornerstone of both DC Comics’ publishing history and its future. As a publisher, we’d be remiss not to expand upon and explore these characters and their stories. We’re committed to being an industry leader, which means making bold creative moves.”

Jim Lee, by the way, is one of the men responsible for last year’s New 52 “reboot.” In fact, he is the man who created this illustration for the first issue of the new Justice League title:

That image in itself does more to rebut Mr. Lee’s disingenuous “bold creative moves” palaver than I ever could.

An “After Watchmen,” however, might have actually been something “bold.” Maybe Richard Nixon took the opportunity of the giant Cthulu vagina appearance to promote his own version of the PATRIOT Act, with the government becoming all the more oppressive. Ozymandias might attempt to further muck things up by creating a grand plan to run for president himself, and steal the election to ensure his victory. Once in office, Ozymandias finds himself doing all the same things that Nixon did, only bigger. Building super drone machines to bomb the hell out of Middle Eastern countries, for instance. Bailing out his corporate friends. Using espionage laws to persecute those who tried to blow the whistle on the whole giant Cthulu vagina conspiracy. Perhaps then Dr. Manhattan returns from exile, and is forced to actually take a moral stand once and for all — is he with Ozymandias, or against him? That’s just off the top of my head for crying out loud, and I’m already more interested in that than, you know, what the Minutemen did during World War II.

II. The Judge of All the Comics

Alan Moore is unhappy about the existence of Before Watchmen.

That’s a bit of an understatement, actually. Mr. Moore is very, very unhappy about the existence of Before Watchmen.

The entire project has been controversial since rumors of its existence began appearing back in 2010, although not for the reasons I’ve outlined above. Rather, the questions have largely swirled around whether the most highly-regarded graphic novel of all time should be left alone, and Mr. Moore’s resistance to the project.

For Mr. Moore, the trouble started back when he signed the original Watchmen contract.

That was the understanding upon which we did Watchmen–that they understood that we wanted to actually own the work that we’d done, and that they were a “new DC Comics,” who were going to be more responsive to creators. And, they’d got this new contract worked out which meant that when the work went out of print, then the rights to it would revert to us–which sounded like a really good deal. I’d got no reason not to trust these people. They’d all been very, very friendly. They seemed to be delighted with the amount of extra comics they were selling. Even on that level, I thought, “Well, they can see that I’m getting them an awful lot of good publicity, and I’m bringing them a great deal of money. So, if they are even competent business people, they surely won’t be going out of their way to screw us in any way.”

In the long and very interesting interview from which the above was cut and pasted, Moore states that he didn’t read the contract “very closely,” because of the previous relationship he’d had with DC. They were the company that brought him over from England, where he’d written comics for 2000AD, Warrior, and Marvel UK. He worked on titles like Marvelman, which he turned into a deconstruction of the superhero genre, and Captain Britain, which he turned into a deconstruction of the superhero genre. I’m oversimplifying a bit, for effect. Len Wein hired him to write the Swamp Thing series, and he was essentially given free reign to reinvent the character and the comic, turning it into a more overt horror comic, a deconstruction of horror comics, and a deconstruction of comic book swamp creatures. Again, I’m oversimplifying, but just a bit.

It was at this time that Mr. Moore submitted a proposal for a miniseries in which he would use characters that DC had recently purchased from Charlton Comics, including the Blue Beetle, the Question, and Captain Atom. DC’s executive editor at the time, Dick Giordano, liked the pitch, but he rather quaintly worried about what the story would do to the characters, and DC’s ability to exploit them later:

MOORE

In my late teens, as I was daydreaming about becoming a comic-book writer, I found myself thinking about a line of ’60s superheroes published by Archie Comics: What if one of them was found murdered, and through the investigation, you explored the world they lived in? I intended to resurrect that idea with the project that became Watchmen. But when we submitted the proposal, DC realized their expensive characters would end up either dead or dysfunctional.LEN WEIN (Watchmen editor)

Dick Giordano, DC’s executive editor, had worked at Charlton and may have been attached to the characters. But he liked Alan’s story, and asked him to reconceive his pitch with new characters.

This was a purely merchandising concern, although, given what DC has done with the characters since (reboots! reimaginings!), it seems absurd. And it’s not as if DC hadn’t “rebooted” characters before — their Silver Age Flash, Green Lantern, Hawkman, and Atom were all reboots.

For whatever reason, DC wanted Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons to create a whole new set of characters, and a whole new continuity for them. Mr. Moore, who clearly put a lot of trust in DC, agreed.

This actually shows another flaw with both the original Watchmen book, and with the Before Watchmen spin-offs. The moral center of the book is Rorschach, who is portrayed as a callous, vicious, disturbed man whose desire to punish the guilty grew out of his abusive childhood. It was never Mr. Moore’s intent to have Rorschach be the moral center of the book. Mr. Moore again trespassed on his work by saying,

There were certain areas of the comic-book world where Watchmen did cast a black, bleak shadow…. I originally intended Rorschach to be a warning about the possible outcome of vigilante thinking. But an awful lot of comics readers felt his remorseless, frightening, psychotic toughness was his most appealing characteristic — not quite what I was going for.

Of course the artist’s intention means nothing once the end result has been released. And in the end, every character in the book is either venal (Ozymandias, The Comedian), a moron (Dr. Manhattan), or both (Nite Owl, Silk Spectre). Only Rorschach operates with a clear moral compass that is independent of politics, and cannot be compromised by the vague promise of “the greater good.” And, given that Ozymandias’s plan is stupid and immoral, the fact that Rorschach would rather die than give his approval shows that he is the only character in the book with a clear idea of right and wrong.

That happens to be what people responded to about Rorschach.

The Watchmen project began as a pitch involving Charlton characters. Rorschach was intended as a stand-in for The Question, a character created by the great Steve Ditko in 1967 as a backup feature in Ditko’s Blue Beetle comic, which was itself a reboot of a character who’d been around since the 1940s.

Mr. Ditko is an Objectivist. Not only is he an Objectivist, but he is an uncompromising comics creator. The former Marvel Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter describes working with him:

[I]f it was a hero that had any flaws, he wouldn’t touch ’em. “Heroes don’t have flaws. Heroes are heroes.” I’m like, “Oh, geez, you did Spider-Man. He had flaws.” He said, “Well, he was a kid then. It’s okay. He hadn’t learned anything yet.”

…

When I went to DEFIANT I asked him to describe to me the perfect kind of character. I thought I created that when I did the Dark Dominion thing and he agreed to draw it and he got about halfway into it and he came in and dropped it on my desk and said, “I can’t do this.” I said, “Why not?” He said “It’s Platonic, and I am a Aristotilian.” I said, “What?” He had to explain that one to me and he said, “Well, Plato thought there was the real world and then this invisible world and I’m Aristotilian—I believe that what you see is what you get. That’s all there is. Reality. This story has a substratum world and I’m not drawing it.” I said, “Oh…” (Chuckle.)

The Question was created as a reflection of Mr. Ditko’s philosophy. The character would help people in need, and investigate crimes, but he also left people to deal with the consequences of their actions. When DC incorporated the Charlton characters into their regular continuity, they didn’t quite know what to do with him, so they didn’t even try to reflect Ditko’s vision. In the series that Dennis O’Neil wrote beginning in 1987, he was reimagined as a follower of Eastern philosophy. In the 2005 miniseries by written by Rick Veitch, he was reimagined as an “urban shaman” with an ability to detect “chi energy.” In the “Justice League Unlimited” animated series he was reimagined as a paranoid conspiracy theorist. Finally, in the miniseries 52, he was shown to be completely aphilosophical, just another superhero who fights crime, who, dying of lung cancer, recruits a female cop to take his place.

In other words, most of the creators that DC has employed for the 30-odd years that they’ve owned the character have been unable to even attempt to get inside the head of an Objectivist, so they have turned him into something, anything other than what he really was, in order to make it easier on themselves.

Mr. Moore tried to present a version of The Question that was true to his roots, at least as Mr. Moore saw them.

With Steve Ditko, I at least felt that though Steve Ditko’s political agenda was very different to mine, Steve Ditko had a political agenda, and that in some ways set him above most of his contemporaries. During the ’60s, I learned pretty quickly about the sources of Steve Ditko’s ideas, and I realized very early on that he was very fond of the writing of Ayn Rand.

…

I had to look at The Fountainhead. I have to say I found Ayn Rand’s philosophy laughable. It was a “white supremacist dreams of the master race,” burnt in an early-20th century form. Her ideas didn’t really appeal to me, but they seemed to be the kind of ideas that people would espouse, people who might secretly believe themselves to be part of the elite, and not part of the excluded majority. I would basically disagree with all of Ditko’s ideas, but he has to be given credit for expressing these political ideas.

In a simultaneously condescending and magnanimous way, Mr. Moore is saying that he was trying to show, in Rorschach, the end result of the Objectivist philosophy. This is fine for Mr. Moore, who has admitted that he was trying to make a political statement with Watchmen. Objectivism is unappealing to him, and he used his own series to present his view of the philosophy.

Rorschach is one of the Before Watchmen miniseries titles. In 30 years, no one was able to capture the essence of The Question the way Ditko did (in fairness, Frank Miller used him effectively as a pedantic libertarian in The Dark Knight Returns), but the Question simulacrum, the parody, the exaggeration, the Objectivism object lesson, Rorschach — DC will treat that character with the proper respect.

The same goes for Nite Owl. Why bother, when you have Blue Beetle? Well, Blue Beetle got rebooted, which is fine, actually, since Nite Owl was pretty much just a Batman knock off anyway. But that raises another point — why bother creating a new prequel series about a character who was a simulacrum of a knock off? Because, this is mainstream comics, and that is the kind of stuff they do. And when they do it, they pat themselves on the back and call it “bold.”

When the original issues came out, they were an immediate commercial and critical hit. Along with Mr. Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, it set a new standard for the mainstream comics industry. But Mr. Moore’s relationship with DC began to sour. Issues with his Watchmen contract, coupled with DC’s implementation of a “ratings system,” caused him to break with the company in 1989. He vowed to never work for them again.

Since then, Moore worked variously at his own publishing house, smaller independent publishers, and for larger companies like Image. In 1998, one of the Image partners, Jim Lee, gave him his own publishing imprint under his own Wildstorm Productions. There, Moore created The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen with artist Kevin O’Neil, and Promethea with JH Williams III, among many others. But.

Mr. Lee sold his Wildstorm Productions to DC. So, Mr. Moore was back to working for DC Comics, a state of affairs he tolerated because “there were too many people involved to back out of the project.” Plus, Mr. Lee apparently assured Mr. Moore that he would suffer no editorial interference from DC. However, this turned out to be not true.

So Mr. Moore is angry with DC Comics, and with Mr. Lee. Adding to that anger is his attitude that Watchmen is a self-contained work of art that should not be touched for any reason, most especially as part of a cynical corporate moneygrab.

His overarching beef is with what he regards as corporate propensity to alienate the very talent that could keep the work evolving, preferring instead to squeeze new revenue from aging assets.

“It seems a bit desperate to go after a book famous for its artistic integrity. It’s a finite series,” says Moore. “Watchmen was said to actually provide an alternative to the superhero story as an endless soap opera. To turn that into just another superhero comic that goes on forever demonstrates exactly why I feel the way I do about the comics industry. It’s mostly about franchises. Comic shops these days barely sell comics. It’s mostly spin-offs and toys.

“…I would have thought, from a DC perspective, that’s it’s a lose-lose perspective, unless they did something better or as good as Watchmen. But realistically, that’s not going to happen, otherwise it would have happened before.”

Looking at DC’s aforementioned New 52 reboot, it would seem that Mr. Moore has been proven correct. But is that simply a symptom of the industry in general? Since its beginnings, comics were floppy pamphlets featuring characters that appeared serially. One might wonder what exactly it was that Mr. Moore expected when he started working a major mainstream publisher. Mr. Moore could have, if he’d really wanted to, done a Watchmen like book at a publisher like Eclipse, or First.

He stayed at DC. He wanted to use the Charlton characters. He wrote stories with Batman and Superman. He even pitched an EVENT COMIC called Twilight of the Superheroes. And, by his own admission, Mr. Moore didn’t even read the contract he signed. So where does he get the right to complain?

III. Watch(men)maker

On his Byrne Robotics forum, the great John Byrne, writer and illustrator of some of the best X-Men, Fantastic Four, and Superman stories of the last 30 years, wrote of Alan Moore and Watchmen,

In WATCHMEN, Moore inverted — I might say perverted — pretty much everything the superhero genre is all about. He was not the first to do so, but WATCHMEN was the first time we got it all in such a concentrated dose. Largely, this seems to have happened because Moore is very much a one trick pony. The one trick works for him and his fans, so no problem there, I guess.

and,

I read it twenty years ago (closer to 25, really!) and I was not impressed. I loved Dave Gibbons’ art, but I found the story (if it can really be called such) increasingly hard going, and when we came to the revelation that Rorschach had been crazy even before he put on the costume, I gave up. It was all too negative and nihilistic, and completely at odds with what superheroes are supposed to be. Like using a baseball bat to beat somebody over the head. Sure, you CAN do it, but does that mean you SHOULD?

Incidentally, it is extremely disingenuous of Moore to say he wishes the comic industry had “moved on”, since he himself has not.

Mr. Byrne’s point is that Mr. Moore is a deconstructor, that he uses the conventions of the superhero genre as a means of commenting on the absurdity of superheroes, and of the noblest ideas of heroism. Unlike Mr. Ditko’s, Mr. Moore’s hero characters tend to be flawed — suffering some sort of mental corruption or indulging in some sort of sexual fetish.

Mr. Moore’s stories fixate on certain superficial and absurd conventions of superheroes, such as for instance, the skintight leotards and capes. We know that the reason that superheroes wear skintight outfits is because clothes are difficult to draw. It’s much easier to simply draw a nude form then put some underwear over their naughty bits, color them blue, and then add on a cape to more easily show movement. The skintight outfit was borne of a creative shortcut by the artists.

Yet Mr. Moore, and many others, projecting themselves into the world in which superheroes inhabit, wonder why it is that anyone might be motivated to wear skintight outfits. If you saw someone prancing about in a skintight outfit, leaping from building to building, you might wonder that yourself.

“I’m fighting crime!” the superhero replies, when asked about it.

“Okay,” you answer back. “But, why are you fighting crime in that particular outfit?”

Mr. Moore provides his own, explicit answer to that question in the seventh issue of Watchmen, when Nite Owl and Silk Spectre copulate in Nite Owl’s Owlship, or whatever it was called. Prior to that scene, Dan Drieberg had been impotent physically and emotionally.

Mr. Moore has his defenders, who strongly disagree with Mr. Byrne’s assessment. In an astoundingly tin-eyed review (titled “Behind the Mask” — ain’t that clever?) of the Absolute Watchmen collection in the New York Times, someone called Dave Itzkoff wrote,

But “Watchmen” has another legacy, one that Moore almost certainly never intended, whose DNA is encoded in the increasingly black inks and bleak storylines that have become the essential elements of the contemporary superhero comic book-a domain he has largely ceded to writers and artists who share his fascination with brutality but not his interest in its consequences, his eagerness to tear down old boundaries but not his drive to find new ones.

I call Mr. Itzkoff’s review “tin-eyed” not just because of the silly sentences pasted above — what “boundaries,” exactly, was Mr. Moore looking for, and why on earth would any creative person want to find such things? — but because he characterizes Ozymandias’s “world’s stupidest thing” as “a bargain that keeps mankind safe while utterly compromising any right they have to call themselves heroes.”

Mr. Itzkoff apparently believes that somehow the simulated giant Cthulu vagina invasion would have been an effective tool in keeping “mankind safe.” Someone who believes that Mr. Moore is trying to find new boundaries might come to such a conclusion, but it makes sense only if you accept the notion that well actually I can’t think of any circumstance under which that makes sense so just forget I started writing this sentence.

Just before the film adaptation was released in 2009, a man called Matt Selman writing at Time‘s TechLand wrote a rather hyperbolic mash note to both the film and the book.

What I am going to write about is the emotional experience of seeing a piece of literature with which I have an intense personal connection LITERALLY COME TO LIFE. It’s a serious freak-out.

I’m not alone in having bonded with the Watchmen comic book back when it was first published. But in 1986, I sure felt like I was. Barely anyone in my high school even knew who Wolverine was, let alone Rorschach. Gradually, however, the awareness of the Watchmen graphic novel has spread from a small group of comic book readers to become a major cultural touchstone for an entire generation. It’s the common ground uniting almost everyone in my creative community.

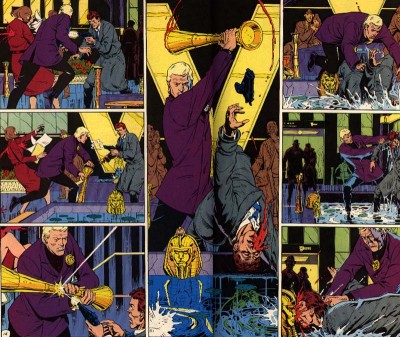

Please note that Mr. Selman didn’t just read Watchmen, he bonded with it. Like a friend. I get that. It’s certainly possible to feel an emotional attachment to works of art. But Watchmen, while superficially quite beautiful, is, as a work, hostile to sentiment. It is a triumph of form over function. It is full of decadent games that distance the reader from any genuine emotional connection. Take for instance the famous fifth issue titled “Fearful Symmetry.” At the dead center of that issue, where the staples held the original issue together, we get this two page layout:

Get it? It’s symmetrical. And the issue is titled “Fearful Symmetry.” The fifth issue of a twelve issue series is titled “Fearful Symmetry,” and the entire issue is deliberately laid out symmetrically. Anyone reading the issues when they came out would have noted this and taken it as a signal to —

look for symmetry. Okay. Um. What are we supposed to do with that, exactly? Well, here’s Stuart Moulthrop of the University of Baltimore, musing on the topic:

But in Watchmen there are always many levels of meaning. Note that this two-page spread comes in the middle of Chapter V (i.e., where the staples would have gone in the monthly comic). This is the middle of the story, the point of convergence where right and left, what you’ve seen and what you’re about to see, come together. “V” indeed. Could this sequence be the pivot point or narrative center of Watchmen as a whole? No, since the mathematical middle of this 12-part epic comes at the end of Chapter VI. Typically, and in keeping with Watchmen‘s deep thematic about time, Moore has brought us to a center which is not a center. We’ve come to the middle too soon.

Likewise, is this a “V” or an “X”? Look at the center panel of pages 14-15 again. Notice how the lower part of Veidt’s body (victim turned killer) and the upper part of the assassin’s body (killer turned victim) form the lower half of an “X.” There are multiple planes of symmetry here, as in Dr. Manhattan’s crystal palace on Mars (see chapter IX). Things are more complex than we might suspect. And what’s the difference between an “X” and a V”? Well, continuity, for one thing. “V” indicates convergence on a single point: the moment of revenge, or vendetta, for instance. “X” indicates a crossing pattern or chiasmus. There is a meeting, a crossing-over, after which two lines once again diverge. If “V” was the operative geometry of V for Vendetta, does “X” mark the plot (as one of my students has written) for Watchmen?

All well and good, but what if Mr. Moore and Mr. Gibbons were willing to put so much thought and effort into creating symmetrical panels and layouts for the fifth issue of their twelve issue series — everything is off balance? — then why couldn’t they think through the implications of the “world’s stupidest thing”? Why is so much thought given to the structure of the work, but not the story?

The answer is that ultimately, Watchmen is about structure, and this gets to the second part of Mr. Byrne’s complaint of “the story (if it can really be called such).” The book was originally published in 1986 and 1987 as 12 (mostly) monthly issues. In other words, in the traditional style in which comics have always been produced. The book is as much about the form of comics as any other issues it might cover, such as what makes a hero, or politics, or the threat of nuclear war. In fact, the structural issues overwhelm all other considerations, and Mr. Moore and Mr. Gibbons allow their decadence to overtake them. These simulacra exist for the purposes of their experiment in traditional comic book narrative. Earlier I said the book was self indulgent, and this is why. That same academic I quoted above tellingly reveals the secret to Watchmen’s success, and it’s problems, with one single sentence:

On one level, this is clearly Alan Moore having a dark sort of fun with his fans.

Watchmen is a Nabokovian work. It’s in the tradition of Sterne and Cervantes and Van Eyck. This is it’s not-so secret. It is a deliberately obfuscatory and arcane game between the author and the reader, in which the two parties attempt to outsmart one another, and everyone feels flattered in the process. The plot obviously doesn’t work — it’s not meant to. The plot doesn’t matter. What matters is that Mr. Moore told his story, and played all of his tricks and dropped in all of his references and symbols, in a traditional comics publishing format. That he was able to get DC, one of the two major publishers of comics and the owners of Superman, the character that basically jump started the comic book industry, gives the work that much more resonance.

When we look at those original Superman stories from the late 1930s and early 1940s now, we can clearly see the historical context. Superman was a New Deal believer. He was a reaction to the Great Depression. He was a reflection of societal anxiety, and a wish-fulfillment fantasy. The original creators weren’t thinking about any of that. Read those stories and you’ll see they weren’t thinking about much of anything besides telling a story. There’s no continuity. In one story, Superman acts like a belligerent child. In another, he’s a righteous adult. Whatever the story required, that’s what he was. This was storytelling borne out of enthusiasm and youthful idealism. They were building an entirely new form, they weren’t thinking about meaning, nor were they concerned with structure. They were trying to fill their 12 or 13 pages with an exciting story.

Superman was an aspirational figure. The line on him is that his alter ego, Clark Kent, is the everyman that made the demigod relatable to the reader. Sure, he had trouble getting a date with Lois Lane, but that was always because he was tricking her about his real nature in order to sneak off and change into Superman. Sometimes he got chewed out by his boss, but that was, again, because of his super alter ego. He still had a profession at which he excelled. He dressed nice, he was smart and articulate. Depending on the story, he was well-off enough to keep extra apartments around town to hide witnesses to mob hits, or whatever. For all his supposed relatability, Clark Kent was as much an aspirational figure as Superman.

The next major superhero character to make it big, Batman, was even better (or worse): When he wasn’t out beating up villains, he was a millionaire playboy for crying out loud. Where is the relatability there? Superheroes, whether in their leotards or their three piece suits, were never “relatable,” in the beginning.

Fifty years later, when the first issue of Watchmen appeared, the world of mainstream comics had changed. For one thing, in 1953, the Mad comic book (Mr. Moore has called Harvey Kurtzman’s Mad “the best comic ever“) had totally demolished the conventions of superhero comics in the classic 8-page “Superduperman!” story. For another thing, Steve Ditko’s and Stan Lee’s Spider-Man presented an ongoing character who had trouble paying his bills on time, was reviled by the people he was trying to protect (including his own aunt), and was motivated by guilt over the death of his uncle. Now, he was a genuinely relatable character. And, Neal Adams and Denny O’Neil had re-invented Batman as a “gritty,” “dark” superhero, after being treated as a kitschy joke for most of the 1960s. Moreover, Steve Gerber’s Defenders had presented a “non-team” of second string Marvel heroes, including the Hulk, Doctor Strange, and Silver Surfer, as a group of dysfunctional, bickering, and occasionally petty — but ultimately charming — neurotics.

Watchmen was part of that same continuum. In many ways, its characters were so relatable that they were unrelatable. They were so neurotic they were pathological. They were so dark and gritty they were terrifying, and the audience therefore didn’t have to relate — the could actually feel superior. But even more important than that, Watchmen was an attempt by an author to impose meaning on his own work. Watchmen examines itself as it goes along. All of that symmetry is for a very deliberate purpose. Symmetry is a tool of deconstruction. It’s Watchmen‘s structure that makes it so successful. It’s certainly what I responded to when the issues first appeared. And as we’ve already seen, Mr. Moore isn’t against trespassing on the work years later, either. Control over the story and its interpretation is the most important consideration.

In that same interview cited above, in which he discussed his problems with Steve Ditko’s Objectivist philosophy, Mr. Moore also said,

Steve Ditko is completely at the other end of the political spectrum from me. I wouldn’t say that I was far left in terms of Communism, but I am an anarchist, which is 180° away from Steve Ditko’s position. But I have a great deal of respect for the man, and certainly respect for his artwork, and the fact that there’s something about his uncompromising attitude that I have a great deal of sympathy with. It’s just that the things I wouldn’t compromise about or that he wouldn’t compromise about are probably very different.

Mr. Moore calls himself an anarchist, yet his most famous work is a paean to the imposition of order over chaos. Ozymandias et. al. are willing to kill to maintain what they see as a necessary social order, while Mr. Moore and Mr. Gibbons rigidly adhere to their structure, eschewing caption balloons in favor of snippets from Rorschach’s diary, and subjective panel images in favor of playing their dark symmetry games. Watchmen could have used more of the “anarchist” Moore in its approach. So, too, could the current Before Watchmen creators.

IV. At Midnight, all the Agents Snarked…

So DC Comics has decided to go backward into this world that is very specifically and eccentrically Alan Moore’s and Dave Gibbon’s. They’re not extending the story out, they’re retreating into something that exists in Alan Moore’s brain. Try to imagine someone producing a prequel to The Life and Adventures of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, or Pale Fire.

A lot of people have said it’s “hypocritical” for Mr. Moore, who uses characters created by other authors, to complain now that the world he co-created is being used by DC in this manner. No less an author than J. Michael Straczynski, who is scripting two of the Before Watchmen series, said in an interview,

Leaving aside the fact that the Watchmen characters were variations on pre-existing characters created for the Charleton [sic] Comics universe, it should be pointed out that Alan has spent most of the last decade writing very good stories about characters created by other writers, including Alice (from Alice in Wonderland), Dorothy (from Wizard of Oz), Wendy (from Peter Pan), as well as Captain Nemo, the Invisible Man, Jeyll and Hyde, and Professor Moriarty (used in the successful League of Extraordinary Gentlemen). I think one loses a little of the moral high ground to say, “I can write characters created by Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle and Frank Baum, but it’s wrong for anyone else to write my characters.”

He has also said, during a panel discussion of the miniseries,

Straczynski addressed the online criticism of Alan Moore and said he got it on an emotional level. “Alan Moore is a genius. No question,” said Straczynski. “On the other hand, he’s been using characters like the Invisible Man, Peter Pan, Jekyl and Hyde in what one fan basically called fan fiction — in ways their original creators probably wouldn’t have approved of. … You stand on a slippery slope when you use the moral high ground.”

Mr. Straczynski clearly takes umbrage at the use of the “moral high ground.” And you can almost hear the sneer in his voice over that “fan fiction” line. But do these arguments carry any weight, in this context? Superficially, at least, it seems that Mr. Straczynski and all the other online commentators who have made this argument do have a point — why should Rorscharch be sacrosanct, but Captain Nemo fair game? Mr. Moore has himself addressed this issue:

Swamp Thing had been, I suppose, created by Len Wein (although in retrospect it really wasn’t much more than a regurgitation of Hillman Comics’ The Heap with a bit of Rod Serling purple prose wrapped around it). When I took over that character at Len Wein’s suggestion, I did my best to make it an original character that didn’t owe a huge debt to previously existing swamp monsters. And when I finished doing that book, yes, of course I understood that other people were going to take it over. That went for characters that I had created, like John Constantine. I understood that when I had finished with that character that it would just be absorbed into the general DC stockpile……The thing was, that wasn’t what we were told Watchmen was.We were told that Watchmen was going to be a title that we owned and that we would determine the destinies of. If we didn’t want there to be more than 12 issues, there wouldn’t be more than 12 issues. We thought we controlled and we owned these characters. Now, there is a huge difference between the two of those things.

…With regard to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, what I’m doing with that is a kind of literary game that has been going on as long as books have been around.I mean, it probably started with whoever came up with Jason and the Argonauts, who thought, “Hey wouldn’t it be great if we had a sort of Justice League of ancient Greece. And we got Hercules and Jason and all of these other characters and you know…”More recently, you have authors like Edgar Allan Poe. He writes The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. Jules Verne thinks it’s great, so he writes a sequel to it. H.P. Lovecraft–he likes the same story, so he writes his conclusion to it in At the Mountains of Madness.I don’t think any of these people would have minded because they were all good writers who were all bringing something new to the mix. They weren’t exploiting the original works. Jules Verne called his novella, The Ice Sphinx or Le Sphinx Des Glaces. He didn’t call it The Return of Arthur Gordon Pym.So, what we’re doing is taking these characters that are mostly in the public domain. If they’re not in the public domain, they are only referred to glancingly, as a bit of a cultural joke.It’s a bit different to bringing out a comic called Rorschach.…But there’s no real comparison. In The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, I am not adapting characters. I am flat out stealing them in what I think is an honorable way.…There wasn’t any point in simply recycling these characters. I think that our interpretations of them have put them into new contexts, and have probably been truer to the originals than any of the official adaptations. We’ve had several probably decades of people who probably thought that Captain Nemo looked like James Mason. No, he was an Indian Prince.

Mr. Moore’s reasoning is a bit convoluted, drawing as he does a distinction between public domain characters, versus those owned by corporations, but his point is that he feels, and he has decades worth of evidence to back him up, that nothing new is being done here. See the emphasis above.

Also note his use of the term “literary game.”

Mr. Moore has actually answered this question better, and with more eloquence, in an interview promoting last year’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Century: 1969 book:

Fan writers have contributed to a kind of literary incest. And God bless fans! This is not a condemnation of comics fans. But they are comics fans who have got into the exalted position of controlling the destinies of their favorite characters, and what they mainly want to do is refer to some story from their childhood, which itself probably referred to a story 10 or 20 years before that. Or given the, what, 80 or 90 years of continuity of some of these characters, there is all these incredibly sprawling incidents that fan writers are going to refer to.

And this is going to result, as in any case of incest, in a depleted gene pool. You’re going to have stories that are less and less relevant to a diminishing readership, that refer to a story that referred to a story that tied up some bit of continuity that appeared in some issue of Action Comics published way before we were all born.

I think the current state of superhero comics could be squarely laid at the door of the comics industry. I think they don’t quite realize what they had, and they tried to strip-mine the concept in all sorts of ways, and didn’t put anything into it. They removed the genuinely creative people from the mix, who had provided all the ideas that both companies are still trading on all these years later. And gave custody of the industry to people who were fans of those who had just been fired. Over here, we might call that scab labor, depending on how we felt. These are my basics thoughts on superheroes.

Mr. Moore is as much concerned with the state of mainstream comics as he is with the state of his creations. Yes, it is self-serving, but can anyone look at what’s been happening with comics since the publication of Watchmen and do anything but despair? Watchmen could have been the rallying cry for genuine boldness and experimentation in comics. But with few exceptions, the books have gotten less and less relevant. Watchmen continues to sell. Rather than attempt to find and fund the next Watchmen, whatever that might be, DC Comics is moving backward, yet again, into the very eccentric world of a creator whose work is structural, not emotional, and very much specific to him.

Or, Mr. Moore could have quoted Oscar Wilde, who said,

“Consistency is the last refuge of the unimaginative.”

Mr. Moore doesn’t have to answer that particular charge, but he makes a good argument. Mr. Moore is at least attempting to employ these characters to say new and different things about the times in which they were created, and as tools to expand upon his own creativity. Ironically, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen books, the first two collections, at least, are among Mr. Moore’s least decadent. They have a real buoyancy and a sense of fun that is conspicuously missing from Watchmen.

Which brings up another problem with Watchmen. It’s just so damned dour.

It’s rigidly constructed, very much on purpose, but all that symmetry, and the strict adherence to the nine panel grid layout, is draining. On top of which, the material is overwhelmingly bleak. As we’ve already seen, the moral center of the book is sleazy, smelly man who eats cold beans from a can and writes disturbing notes in his journal. The only hope to “keep mankind safe” is a ridiculous and completely unworkable plan to simulate a giant alien Cthulu vagina invasion in which millions of innocent people are murdered.

If you’ve read the book, can you think of any light moments in it? Maybe the first issue’s conversation between Dan Dreiberg and Laurie Juspeczyk regarding Captain Carnage, the “villain” who liked to get beat up. But how many such moments exist in the book? The “dark sort of fun” of the book comes from trying to follow along with Mr. Moore’s games. Watchmen makes you feel clever, because it is itself a clever book. When I was young kid, reading those Watchmen issues as they were published, I certainly felt clever. More than that, I felt as if I were having my cleverness validated. Like Mr. Selman quoted above, I bonded with Watchmen. Unlike him, however, I did not form any lasting emotional attachment to it, because the bonding wasn’t emotional.

The comforts it provides are cold.

V. (or is it an “X”?) A Depleted, Irrelevant World

Mr. Moore has expressed concern over the mainstream comics industry’s “depleted gene pool” and stories that are “less relevant to a decreasing readership.” If anything, that process has accelerated since the publication of Watchmen. The decadent games so brilliantly displayed in Watchmen and in Mr. Moore’s other works, have influenced an entire generation of authors who believe that showing how clever they are is a substitute for telling fresh stories.

Examples abound, but I’ll limit myself to two which were covered by mainstream news media outlets. The first was the “death” of the Marvel Comics character Captain America. In the New York Times obituary for the character (I’m not kidding, the New York Times ran an obituary for him, think about that the next time someone sends you a link to a David Brooks or a Paul Krugman column), they said,

Captain America, a Marvel Entertainment superhero, is fatally shot by a sniper in the 25th issue of his eponymous comic, which arrived in stores yesterday. The assassination ends the sentinel of liberty’s fight for right, which began in 1941.

The last episode in Captain America’s life comes after the events of “Civil War,” a seven-issue mini-series that has affected nearly the entire line of Marvel’s library of titles. In “Civil War,” the government began requiring superheroes to register their services, and it outlawed vigilantism after supervillains and superheroes fought during a reality show, accidentally killing hundreds of civilians. The public likened the heroes to weapons of mass destruction that must be controlled.

A casual reader might be forgiven for thinking that is the end of that, that the assassination is real and that Captain America had in fact been “fatally shot.” But in comics, RIP stands for Reboot in Perpetuity, and the dead don’t stay dead for long. These aren’t characters so much as Intellectual Property to be exploited for as long as the (ever evolving) copyright law allows.

But it’s not just that Steve Rogers, the original Captain America, was resurrected. It’s how he was resurrected that serves to prove Mr. Moore’s point. Here is a fraction of one synopsis of the miniseries in which he returned, Captain America Reborn,

In Captain America Reborn, As the machinations of the Red Skull continue despite the intervention of the new Captain America, Black Widow and the Falcon, he and Arnim Zola reveal to an astonished Norman Osborn that the gun Sharon Carter used to kill Steve Rogers actually froze him in space and time at the moment of his death. That moment of spatial and temporal stasis could be used to bring back his body from any moment in the future via a modified version of Dr. Doom’s time device and Sharon Carter herself, whom they referred to as “the constant.”

At the time of the intended retrieval, Sharon’s actions disrupted the process, resulting in Steve being lost in time and space. He is shown reliving moments of his past, most notably events during the Second World War, badly disoriented and bewildered. While going through the time stream, Steve finds himself back in 1944, at one of the Red Skull’s bases, fighting Master Man. As he begins to fight Master Man, Cap figures out that he has somehow been sent back in time and reliving all of the battles he has fought in over the years. After he defeats Master Man, Steve is then sent to the time he met with President Franklin Roosevelt at the White House.

Is there anyone, outside of that diminishing comics readership, who would be enticed by such a story? But you see, what the uninitiated don’t get is that it’s clever, because Captain America was frozen in the ice in a state of suspended animation just after World War II, and then found in the fourth issue of the Avengers comic book in 1963, and the whole Death of Captain America thing was just an homage to that, and here is an entire miniseries in which we delve into the minutiae of Marvel continuity, and you get the idea.

The mainstream comics event as a deconstruction.

And over at DC, in 2010, Grant Morrison began his “Batman Incorporated” storyline. As the Associated Press (!) reported at the time,

The acknowledgment in the final pages comes as Wayne holds a news conference where he asks those gathered: “Some of you may have wondered … how does a man like Batman afford to constantly update his crime-fighting technology? Where does his money come from?

“Well, the answer is me.”

The confession, Morrison said, is part of a detailed effort that puts into motion a plan for Batman Incorporated, a global network of Batmen from China to Argentina to fight crime worldwide.

Batman Incorporated might actually be the most decadent and baroque comics series ever released by a mainstream publisher. I cannot think of another example of a comic book company allowing one of its biggest properties — and one of the biggest properties in all of entertainment — to serve as a deconstruction of another company’s character, Marvel Comics’s Iron Man.

[Tony] Stark, the man beneath the Iron Man suit, has almost always “admitted” that Iron Man was his dedicated bodyguard, as well as a superhero and member of the Avengers. Stark has gone as far as getting someone else to pilot the Iron Man suit to prove that they were not the same person, as goofy as that sounds. Bruce Wayne appearing on stage and declaring similar things can’t possibly be a good thing, especially when half of Batman’s face is revealed by his mask, and Wayne appears on stage with people who look very suspiciously like his sidekicks, which removes any kind of plausible deniability from the situation.

The idea of a “Batman Incorporated” makes a sort of internal sense in the world of the film “Iron Man 2,” in which Tony Stark declared, “I have successfully privatized world peace.” At the time of that film, the only other Marvel Studios film character was the Hulk. But in the DC Universe, which includes Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, Plastic Man, Aquaman, Black Canary, the Flash, the Doom Patrol, Captain Marvel, the Atom, the Challengers of the Unknown, the Spectre and for crying out loud Superman why would a corporation need to go around recruiting people to work as superheroes?

It gets even more decadent when you realize that Iron Man is awfully close to being Marvel’s Batman simulacrum. He’s a the scion of a wealthy family, the head of a large corporation, who builds himself an outfit so that he can fight crime. Stan Lee, one of the creators of Iron Man, has stated that he was based mostly on Howard Hughes. He’s also stated that he has a terrible memory, so who knows if Batman was a conscious influence on the character. The point is, they bear more than a passing resemblance to each other, and now the one who came before, Batman, is being used to deconstruct the other one.

Part of the elegance of Watchmen is that, yes, it’s a deconstruction of comic book structure and storytelling conventions, but it’s also a stand alone work that can be enjoyed by those who aren’t versed in 70 years worth of continuity. Watchmen actually creates its own continuity, its own backstory, and its own scholarship. You don’t have to know about the Question/Rorschach connection to catch on to the symmetry of that fifth issue of the series, for instance.

DC claimed that one of the reasons for its “New 52” reboot was to clear up all the cluttered continuity and start from scratch, to attract new readers. (Their sales did improve, but how many of those new sales were to people who weren’t already buying comics?) They claim to be launching these Before Watchmen books for much the same reason.

For me it goes back to that window between when the trailer premiered at the end of The Dark Knight and then to the Watchmen movie. We sold hundreds of thousands of copies of Watchmen during that period of time. When you have that much interest, that much excitement – and you know that it’s not the same people buying copies over and over again – there’s something going on in the zeitgeist that makes these characters exciting to people. We’ve tried other ways to build on that, but you can’t really build on it because what people really want to see was more Watchmen. They loved the characters as they were created in that original product.

Do people really want to see more Watchmen? Undoubtedly there are some fanboys who do, but those people are already buying comics anyway. Do the non-comics fans who have read Watchmen want to see more? DC seems to think so, or at least they are pretending they think so. I’m completely unconvinced, for the reasons I’ve outlined here. Ultimately, Watchmen is self-contained not because of its story — its story is nonsensical and ends with a monumental cop-out — but because of its structure. Does anyone really “love” the characters?

They were designed to work in an ensemble piece. They’re in some ways very generic characters–deliberately so. They were kind of archetypal comic book characters, or were intended as such. So, no I don’t think this can work creatively.

VI. The Abyss Gazes On and On

Commenting on a post at Comics Alliance titled “Darwyn Cooke on Why He Initially Said No to ‘Before Watchmen,'” someone called “Prankster” says,

Darwyn Cooke is the only reason why there’s any moral ambiguity about the Before Watchmen project, because he’s actually really talented, unlike most of the other writers involved. But it’s obvious from that interview and others that he knows he’s doing something sleazy and is desperate to rationalize it.

The implication is that, because Mr. Cooke draws and writes in a manner that Prankster finds appealing, he must then have some kind of higher morality. But at the same time, he obviously “knows he’s doing something sleazy.” So, participating in the Before Watchmen project is sleazy, and must be rationalized by the creators involved, but because Mr. Cooke is “talented,” then the project is in fact morally ambiguous.

Or, perhaps, Prankster is thinking how much easier it would be to ignore these new Before Watchmen series, to take a righteous stand against DC’s cynical moneygrab, if only there weren’t a talented person involved in its creation.

Either way, Prankster, and thousands of other fans of Watchmen in particular, and corporate entertainment in general, are trying hard to figure out just what they should do about these series. The Los Angeles Times offers this bleak portrait:

“Watchmen” didn’t just make comic-book history in 1986 with its sprawling, subversive doomsday tale, it became something close to a holy text for comic-book fans. That’s why the publishing news out of New York today will make some purists feel like it’s the end of the world.

…

For some fans, the project will be viewed with deep cynicism because of the absence of the “Watchmen” creators, writer Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons, but others will be intrigued by the fact that the new titles feature some of today’s elite talents, among them J. Michael Straczynski, Darwyn Cooke and Brian Azzarello.

Some will be cynical, but some will be intrigued. I wonder why some can’t be both cynical and intrigued, like me. But then I’m a fairly complicated person.

But there are some people who are untroubled by such moral concerns, as evidenced by the comments on this website. Among them:

Alan Moore is an arrogant moron

Alan Moore defines “grumpy old man.”

I will take Moore far more seriously (in other words not consider him a rather self-important hypocritical blowhard), as soon as I hear that he is on his knees at the graves of Stoker, Verne, Wells, Haggard, etc (not to mention all the folks at Fox Comics) for the “evil” he did them.

While I don’t believe the pre-Watchment stuff will add anything of value, neither will anything that is written now diminish what Watchmen accomplished.

I also can’t help being amused at Moore’s undeniable hypocrisyThe problem with Alan Moore is that he’s just very unlikable. All he does is Whine. Whine and complain. He whined about the movies of League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, From Hll, V for Vendetta, and Watchmen. He’s always whining about DC Comics…I’m just sick of the guy.

Talented writer to be sure….just a really unlikable one.

Do I think ‘Before Watchmen’ is a good idea? No. Not really. Do I want to read it? Again, not so much. But I’m very happy it exists. I just like seeing Alan Moore miserable.

In the comments section of this post, there is a spirited debate between Mr. Moore’s detractors and champions. As the RottenTomatoBot has shown us, commenters are often not subtle. But the decision of a fanboy to purchase the Before Watchmen books is an intensely personal one. Ultimately, that choice belongs to the individual, and whether it is right or wrong depends on whether or not you think it’s any good.

And if they are just a cynical corporate cash grab, then it’s the audience that’s ultimately at fault, because they don’t support the right kinds of books. One commenter on this article, Michael Aronson, says,

“why do they need to fall back on the merits of a franchise”

Because Seaguy, Joe the Barbarian, Spaceman, and more have sold abysmally. Original, new concepts don’t have a foothold in today’s market. They don’t. Sorry. Just how it is.

Same reason that Nintendo slaps Mario, Donkey Kong, and Kirby on new games they develop that aren’t the same as the core series, because as fun as the games are, they might fail without being connected to part of a beloved franchise.

It’s simple financial sense.

And again, here is the cover of the first issue of the rebooted revitalized Justice League comic:

It would be one thing if, in fact, DC were coming at Watchmen “head-on.” But they’re not doing that, not at all. They’re coming at it from behind, like Dr. Manhattan with Silk Spectre, as depicted on the first issue of the Before Watchmen Dr. Manhattan comic.

By creating prequels, they have drained any interest, and any daring, out of something that could actually have been (brave and) bold. They’ve shown once again that, for whatever reason, they just flat out don’t get it. They have proven Alan Moore correct.

Latest posts by Ricky Sprague (Posts)

- Meet the start-ups that are thriving in the current economic recovery - May 27, 2016

- How a Wonder Woman comic from 1942 led to the Great California Cow Exodus of 2012, maybe - November 28, 2012

- A common-sense approach to restoring economic prosperity - November 19, 2012

- New Philip K. Dick novel too absurd to be believed - September 17, 2012

- My 90 Days, 90 Reasons submission - September 12, 2012

Print This Post

Print This Post

“Do people really want to see more Watchmen? Undoubtedly there are some fanboys who do, but those people are already buying comics anyway. Do the non-comics fans who have read Watchmen want to see more? DC seems to think so, or at least they are pretending they think so. I’m completely unconvinced, for the reasons I’ve outlined here.”

In my life, I’ve only really bought two comics. V for Vendetta and Watchmen. I’m not going to become a comic book junkie to read about the backstories of the Watchmen characters. I enjoyed the book, but they don’t mean enough to me to dig deeper into it.

I probably would have enjoyed a follow-on that dealt with the real consequences of the Cthulhu vagina monster incident, though. But it would have only really been well-done from a cynical dystopian libertarian perspective. Which makes me wonder how any author who could end a story the way Watchmen did would be capable of turning his story on its heels and showing that the deus ex machina ending was just a waste of a couple million lives.

Brad, they keep saying that they want to do something bold, that they want to appeal to a wider readership, but then they keep doing… what they’ve been doing all along.

They never seem to really want to try to deal with the consequences of their stories.

My response to Watchmen (short and long term) is much like yours. I do note, however, that at the end the editorial assistant at the magazine was about to pick up Rorschach’s journal, for whatever that’s worth. I think Jon’s exit line and the last panel were Moore’s nod to “best laid plans.”

Ken, I take your point. But I think that Jon/Dr Manhattan’s murder of Rorscharch overrides the possibility of the journal being published in the right wing crackpotty New Frontiersman paper, or Jon’s wishy-washy nothing ever ends dialogue.

Ricky, lots of good stuff in here, really pleased to see it. I don’t see why “Jon/Dr Manhattan’s murder of Rorscharch overrides the possibility of the journal being published.” I think Moore is clearly indicating here that the millions of deaths were in vain and won’t achieve peace, since the whole plot will be exposed when the journal is published.

Thanks, Scott.

Even if the New Frontiersman publishes all of Rorschach’s journal that would change anything. NF is a fringe publication written by and for crackpots. It would be easy for Ozymandias, and the government, to tell everyone that (a) the journal isn’t real, and, (b) even if it was real, everyone knows that Rorschach is nuts (just read the diary — “droppings of lechers”?), and, (c), NF is a fringe publication written by and for crackpots: Prior to the “goddamned, ass-kissing accord,” they really had it in for the Russians, and they’d do anything to stymie peace now, just to sell a few more issues.

The NF editor says, on the last page: “Nobody’s allowed to say bad things about our good ol’ buddies the Russians anymore…” This suggests an extremely complacent media looking to promote a specific agenda. Anything that happens to work against that agenda, and expose the current detente as built on lies, would be rigorously downplayed.

Moreover, the assistant editor, Seymour, isn’t presented as a great intellect. In the book’s last panel, we see him reaching toward a pile of crank mail that includes Rorschach’s diary. We don’t know which piece of mail he grabbed. We don’t know what he did with it when he did.

The plot might be exposed, but I don’t think that would change anything.

Ricky, what you point out makes sense. The publication of Rorschach’s diary might not make a difference — it could be made to go away by Ozymandias if it’s even taken seriously in the first place, and it could be explained away, etc. But doesn’t Moore’s decision to end the book the way he did indicate something about his intent? Even if you could show that, logically, within the story he created, it wouldn’t make a difference, he chose to end the story with the discovery of the diary by a publisher. Maybe Moore didn’t reach the same logical conclusion that you did about what would follow from that discovery. I don’t know. But it would be odd for an author obviously trying so hard to impart meaning throughout the book to end on such a clear implication and for us to dismiss it. Though I guess maybe what’s being dismissed isn’t Moore’s intent. Which brings us back at least to dismissing the significance of the result of the diary discovery within the context of that world, according to your view.

I think that Moore’s intent is to imply that “NOTHING ends, Adrian. Nothing EVER ends,” as Dr. Manhattan says on page 27 of the last issue. And yes, I think that the reader is meant to come away with the idea that the diary will be discovered, and the plot will be exposed to the world.

But I think that’s a giant, steaming cop-out.

This intense, elegantly wrought novel barrels to this silly conclusion, and rather than try to come up something a little less silly, Moore simply says, “Hey, it’s kinda silly, and the whole thing might be found out anyway.”

I also think that, per his trespassing interviews on the subject, Moore didn’t intend for Rorschach to be the hero of the book. But he is.

I’ve been thinking about it a lot lately, and I think that it would have been much better for Moore et al to actually begin with the Cthulu vagina invasion in the first issue, and then work both forward and backward, simultaneously. He could have really cleared up a lot of the book’s plot problems while at the same time playing his structural games. I think that he got stuck on his idea of “what would happen if a superhero were murdered…” and just couldn’t let that go. The real question on which he should have focused should have been, “what would happen if someone had a stupid, murderous plan that he believed would work, but really wouldn’t…”

A great work of art is always open to interpretation, and I happen to think that Watchmen is a great work of art, but the flaws are significant.

“A great work of art is always open to interpretation, and I happen to think that Watchmen is a great work of art, but the flaws are significant.”

Same could be said for V for Vendetta (which I also enjoyed, flaws and all — referring to the collected serial, not the movie).

I suspect that this essay is going to be awesome, but I have some work to do. I will return soon to read it all.

An excellent piece with many great points, but I disagree with your characterization of Moore’s structural experiments as “decadent games”. Moore is very good at structure- I remember an early issue of Marvel Man (sic) which was narrated from the p.o.v. of a severed head during its last seconds of consciousness. This was only revealed very slowly, and provided a spectacular ending. If you have a knack for manipulating structure, then why not push it into new areas and see how far it can go? It is interesting to tell stories in different ways; it also provides different forms of aesthetic pleasure.

Likewise I’d disagree strongly that the book is “cold”. He built up the kid and the newspaper vendor to “expose” or at least demonstrate emotionally the callousness of the powerful towards the powerless. I also remember very strongly the well-written and scenes between Rorschach’s psychiatrist and his wife. John Byrne wishes he could write anything half as good as that, although his more straightforward approach to the intrinsically nonsensical world of superherocs is healthier and more sustainable.

But the ending is definitely nonsense, and the tone is unremittingly bleak. Moore himself has frequently expressed regret for Watchmen’s effect on comics, and tried to rectify things with Supreme in the 90s- a series I enjoyed greatly.

Daniel, thanks for the kind words.

I very much admire the structure of Watchmen. It’s probably the best constructed graphic novel ever published in English. My problem with it is that, there’s nothing else behind it. It’s a work that demands examination, but the story falls apart after only a little thought. And the four characters that you mentioned (vendor, teenager, psychiatrist and his wife) are really the only likable ones in the whole bunch, and I feel that Moore let them down with a resolution that essentially wastes them (as opposed to sacrificing them). Maybe I’m putting too much emphasis on Dr. Manhattan’s murder of Rorschach, but I really think that we’re meant to come away with the idea that Ozymandias’s plan will work.

I say it’s decadent because it feels like the plot and characterizations were of secondary concern, at best — what he wanted was to create a structure. He did a splendid job with that — it’s the Tristram Shandy or Pale Fire of comics (and I think it’s better than Pale Fire). To me, it’s a puzzle that, once completed, leaves me emotionally unsatisfied.

I think it’s a mark of how very good Watchmen is that it can make me this frustrated.

The Marvelman stories you mention are among Moore’s best stuff. That, along with his run on Captain Britain, struck a pretty good balance between story, character, and structure.

I suspect I enjoy John Byrne’s work more than you, but he could just as decadent as anyone — his infamous “Snowblind” issue of Alpha Flight, which featured five pages with no artwork, and his run on She-Hulk, in which she knew that she was a character in a comic book, come to mind. A couple of years back I picked up a trade paperback of the first 8 issues or so of his Fantastic Four run, and I don’t think I read more than half of it.

I’ve read Watchmen maybe 3 times all the way through, and various pages dozens of times. I just wish I was re-reading it for different reasons.

I think what Moore was doing during this period was experimenting with answers to the question, “What would happen in a world with people with incredible power?” and we see in his 1980s work several different answers to this, as sort of thought experiments. Swamp Thing basically retreats from the world to let humanity sort itself out, just making his small corner of it a little paradisal garden; Marvel/Miracleman creates utopia (but it’s suggested that there is a human cost to this); Superman, in Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow, gives up his powers (and says that he was being arrogant to think humanity really needed him); and Dr. Manhattan just leaves to perhaps make his own world. I don’t think Moore was saying that Ozymandias was right to do what he did (and indeed, “nothing ever ends” perhaps hints that he’s deluding himself) per se, just that This Is What Would Happen If People Like This Decided To Save Humanity From Itself. (But even then, the whole thing could come crashing down the moment that journal gets exposed; and also remember, the world is on the brink of nuclear war precisely because of the existence of Dr. Manhattan.) Oh, and in V for Vendetta: Once V has destroyed the system, he leaves it in the common people’s hands rather than trying to create a new system. The ultra-powerful characters (and V, who is an ultra-genius human) who seem to be considered the “wisest” in this era of stories are, I think, generally aimed at removing themselves from the equation altogether, so I’d say that the message Moore has, or the subtext at least, is that the mass of common people should determine their fate rather than seeking someone “higher” or “greater” or whatnot.