Ervin Phillip Ashton: The strange facts in the case of the eerie life

The early 20th century was a golden age of American horror and fantasy fiction. Inspired by the works of such great gothic writers as Bram Stoker, Horace Walpole, Ann Radcliffe, Mary Shelley, Matthew Lewis, and Edgar Allan Poe, a new breed of writer was crafting tales of fancy, suspense, and supernatural horror. In publications like Weird Tales and FantastiFiction, heroic, larger-than-life heroes strode across harsh landscapes to do battle with incredible creatures, witches fought for the souls of the innocent, and a house itself might come to life and attack its tormented inhabitants.

The literature of fantasy, heroism, and horror is one of pure entertainment. The crafters of these stories were interested primarily in offering to readers a diversion from the trials of their everyday lives. In many cases, their literary skills were unequal to their visionary imaginations, and the entertainments they created were considered disposable. It is only a select few of the pulp authors of this era whose names are remembered today, and continue to charm a new generation of fans with a taste for exotic storytelling.

Despite a brief resurgence of sorts in the late 1960s-early 1970s, Ervin Phillip Ashton (EPA)’s is, sadly, one of those forgotten names. This is despite the efforts of my great-Uncle, author, editor, and sometime EPA pen-pal D. August Sprague (DAS). I feel this is an unfair fate for one of the 20th century’s most imaginative authors whose life and supposed death was as confounding as his literary endeavors, and I share my great-Uncle’s enthusiasm for his unusual, occasionally morbid, but always exciting, works.

EPA was born in either 1884 or 1886 (there was a smudge on one of his letters to DAS) in Madison, Georgia. He would spend his entire life in that town, save for one excursion to nearby Atlanta, where he engaged the services of a “notcher” (prostitute), to disastrous results. His entire known life was spent in the same house, which he would share variously with his mother, older sister, grandmother, two great aunts, and four aunts. The only male relative that EPA ever knew was the man that his mother claimed was his grandfather, whom EPA described in a letter to a fellow author as,

“[A] strange, singularly silent figure of imposing countenance who occupied a large medieval chair in the great-room. When I would awake in the morning, fresh a [sic] night of youthful nightmares, there he was, like a gargoyle oppressing the room. When I would turn in at night, grateful to escape into sleep from the pathetic drudgery that befouled my waking life, there he was. Mother said he’d lost three limbs in the War Between the States, which apparently made moving him an exercise dreary enough that, as far as I knew, he never did. And yet, on that fate-filled morning when I awoke to find the house relieved of his presence – dead, according to Mother (she said they’d had the funeral just before I awakened from what I now realized had been an unusually peaceful slumber) – I noticed that there were two large slots in the cushion of the throne he’d used, large enough for a man to place his legs. Perhaps he’d only lost one limb in the war, but I wondered why he should feign leglessness?”

Although he identified himself first and foremost as a writer, his inability to sell his work on a regular basis, coupled with the staggeringly low page rates offered by those few publications that chose to publish his work (in many cases the actual rates offered by these magazines were irrelevant anyway – no payment was ever made), meant that EPA was forced to engage in whatever day jobs he could find. Depending on the time of year and his health, he worked as a ditch digger, a typist, accountant, weed-puller, and medical model.

At 17, EPA made his first professional sale, “The Curious Case of the Oppressed Boy,” to Eerie Worlds. This story was marked by the intense, almost poetically descriptive prose that was to become his trademark.

“From the boy there was not a sonification emanating, save the extravagant pounding of his feverish heart, beating madly against the osseous constrainment of his rib bones. All about him was the maddeningly cachectical oppression which travailed him daily, the shrewlike guffaws reverberating through his very soul, and the odor of tuna fish plagued his nostrils.”

(“Oppressed Boy” was not the first tale he wrote. At 13, the precocious EPA crafted a tale entitled “The Damned Face,” about a 13 year-old boy whose beautiful face is marred by horrible acne whenever he leaves his home. By the end of the story, the protagonist has decided to spend all his time indoors; however, he cannot hide from his curse, even there, and his face erupts with streaming pustules and oozing sores.)

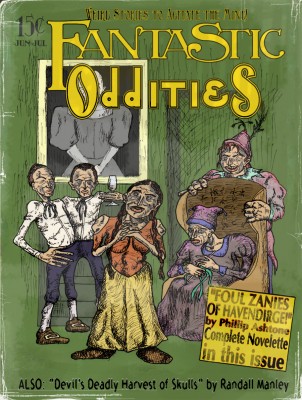

EPA struggled to sell even to the pulp horror magazines of the early 20th century, many of which had strikingly low editorial standards. His stories and occasional poetry generally landed in the back of second- and third-tier horror and mystery titles like Strange Times, The Eerie Nightmares, Eerie Worlds, FantastiFiction, and Fantastic Oddities. In a sad twist of fate worthy of a character in one of EPA’s stories, the one time he managed to get a cover story in one of the pulps (Fantastic Oddities issue number three, cover dated June-July 1919), the editor not only changed the title of the story without his knowledge (from “The Strange Facts in the Case of the Eerie Incident” to “Foul Zanies of Havendirge!”), but also misspelled EPA’s name on the cover.

Cover of the third issue of Fantastic Oddities, from 1919, featuring Ervin Phillip Ashton's story "The Foul Zanies of Havendirge!"

“Zanies” is a classic of sorts; at least insofar as an EPA story can be said to be a “classic.” It opens with a pitiful man, starving, feverish, and beaten, rushing through a wintry forest with no memory of who he is or how he got there. He’s taken in by “zanies,” mentally and physically deformed people who, having never left their family estate, are the end result of generations of incest. The family decides to torture the man, but he turns out to be an Elder of Underwhere, a dark creature of indescribable power from another dimension, the mere sight of whom is enough to induce depraved insanity.

This story features a number of elements that recur in EPA’s stories. It is set, as the editor’s title suggests, in the fictional town of Havendirge, Georgia, where EPA set most of his contemporary horror stories. It features reference to the Elders of Underwhere, ancient beings who split their time between our dimension (called “Overwhere”) and their own “Underwhere.” It features a dark, forbidding house that is not a place of comfort and safety, but of pain and misery. And it features a family cursed by events from the past.

The idea of curses, in particular of family curses, and the inability of an individual to transcend them, is arguably the most obsessive of EPA’s recurring themes. In his story, “The Strange Facts in the Case of the Eerie Incident,” (EPA recycled the title after the “Foul Zanies!” incident) which found a place in an issue of Tales of Fear, an innocent man receives a blood transfusion from another man whose grandfather had many years before murdered the innocent man’s grandfather. The grandson of the killer had been living with the curse of the guilt of that horrible crime (degeneration through the generations); after the transfusion, the curse is transferred to the innocent man, whose life becomes a confusing and horrifying jumble of fear. In “How Many Were There? –My God, There Were 21!,” a man learns that his mother and all of his other living female relatives are part of a coven that has been using their evil feminine magic to curse him at every turn, thwarting his attempts to take control of his own life and find success on his own terms.

Perhaps the most significant of EPA’s “cursed” stories is “House of the 30 Day Curse,” the tale of a young student who leaves his home in an unnamed small town to study at the University of Havendirge. He finds and rents a large house on the outskirts of town for a remarkably low price. For the first few days after moving in, the house seems fine, and he is joyous at his remarkable good luck at finding such a property:

“While not precisely complaisant, the edifice could be said to harbor a great deal of charm within its imposing walls. The illimitable corridors and the towering ceilings offered a remarkable feeling of asylum to the high-strung stripling. The only effect of the habitation which might be considered disobliging was the subliminal but pervasive smell of tuna fish.”

However, as the month wears on, the unnamed student begins to fear the house, which at times seems to come alive. The walls “palpate” and “glisten,” becoming soft to the touch. The odor of fish is replaced by “something coppery,” and eventually the house seems to be screaming inside his head every minute of every day and, locking its doors, refusing to let him leave: “To him it seemed the structure was behaving exorbitantly.” Eventually the student learns that the house is in fact part of the interior of a female Elder of Underwhere; the “house” is merely the parts of her body visible in our world. By the end of the story, the hapless student finally sees the Elder in all her haglike horror:

“To travail ascription of the phenomenon which descended with such violence upon his eyes, molested his eyes, cursed his eyes, forever and anon, would be an affront to the creature itself, and would offer nothing of dignity to the peruser of these words. Let it suffice to say that such an ineffable grotesquerie had never previously been gazed upon by eyes that retained lucidity, and, mayhaps, to have such an abomination described, would imbue the audience with such consternation as to impose the sentence of oppressive insanity!”

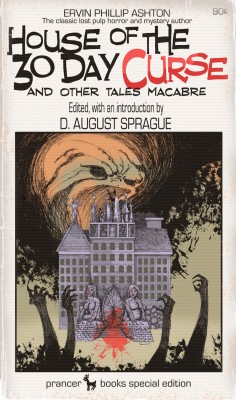

Cover of Prancer Books' 1970 collection of Ervin Phillip Ashton's horror stories and poems, House of the 30 Day Curse. Illustration by the French artist Bonsomme.

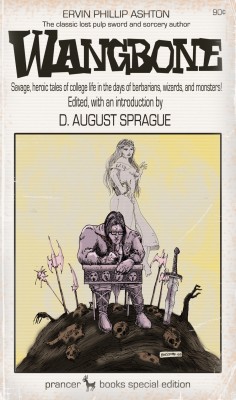

“The Elders of Underwhere” mythos would drive many of EPA’s stories, including those of what must by default be his most famous character, Wangbone the Barbarian. Wangbone was actually Tornon of Poseiborealhu, raised to be a great barbarian warrior by his barbarian parents. But Tornon wanted more – to write, to study poetry and the arts; to attend a university. Thanks to his skill at Tunalarking (a brutal sport resembling water polo, except that the “ball” is a tuna fish that must be captured by one team and killed, earning that team one point and possession), Tornon is offered a scholarship to Upperwhere University. When he pledges a fraternity he is dubbed “Wangbone,” as all pledges are given humiliating nicknames.

Wangbone appeared in 38 of EPA’s stories – the rich world of Poseiborealhuans, magic, and sword and sorcery fantasy provided fertile ground for his imagination. EPA populated UWU’s campus with characters from classic and contemporary (early 20th century) literature and the pulp magazines, including Wangbone’s love interest, the ghost of Cathy Earnshaw from Wuthering Heights, the music teacher Svengali of the novel Trilby, biology teacher Dr. Frankenstein from Frankenstein, and guidance counselor Dracula, of Dracula. In addition, EPA included disguised versions of other famous characters, such as a John Carter character called Don Harter, a Sexton Blake type character called Maxwell Shade, an Arsole Fantüme avatar called Claude Fantom, a version of Oz’s Tik Tok called Doc Tic, a version of Fu Manchu called Mu Fanchu, a Tarzan type called Zar-Tan of the Gorillas, a version of Khlit the Cossack which EPA unfortunately called Slavic Clit, and a Zorro type called Prince Fox.

Typical of the UWU stories was “From the Ice – A Horror!,” in which the UWU’s Ancient Ruins and Obscure Creatures department takes several boats on a long, horrific excursion to the outskirts of the Dire Lands, where, encased in a massive ice floe they find “a vision of most startling distastefulness assailed their eyes!” Many of those who first caught sight of the thing were driven to madness, and “in their madness, attacked their fellows, hacking limbs and spilling innards in the most gruesome manner imaginable.” Those that did not succumb to the madness manage to slaughter those who did, and finally peace once again reigns on the expedition. They then make the highly questionable choice to retrieve “the object of their horror, that they could study the monstrosity and divine with greater precaution the enigma of its conundrum, in the relative comfort of the UWU campus, where combine magic and science to produce a scimagic that would protect them!”

Meanwhile, Wangbone and other fraternity pledges are playing a game resembling soccer against the full brothers as part of their hazing. The difference is that the pledges are forced to play the game on stilts, hindering their movements and accuracy. The losers will be required to clean the fraternity’s stables and toilets for one full week; naturally, those on the stilts have no chance. At this point, the horror retrieved by the Ancient Ruins and Obscure Creatures department has been thawed out, and found to be an indescribable Elder of Undewhere. EPA attempts the most complete description of an Elder to date:

“The unholy gigantean was a therianthropic spectacle marked by atramentous eyes and palpating fibrils that overlayed whatever might have served as its visage and its nether region, and an elongated angular body covered in teats.”

This thing apparently has been in the ice for a long time, and is starved for coital attention, as it goes on a rampage, humping any campus buildings it can find.

It’s left to Wangbone to attempt to defuse the situation, which he does by using one of his stilts as a pole vault to hurl himself into the creature’s nether regions, and he ends up in Underwhere itself:

“[A] topography of madness, marked by phrensy, which no human eye was meant to see. Around him there blurred a visual cacophony of palpating fibrils, of floating horror, of soft, gooey tissue, and the pronounced odor of fish.”

Readers of EPA’s story “House of the 30 Day Curse” would have known that it would be up to Wangbone to find the “Galactic spot,” if he had any hope of making it out of Underwhere alive. Unlike the unnamed narrator of “House,” Wangbone is successful in his quest. However, after being expelled from the creature, his sometime girlfriend, Cathy Earnshaw, finds him covered in fish-smelling goo, and runs away in sadness and disgust at what she fears is his unfaithfulness.

Cover of Prancer Books' 1970 Wangbone mass market paperback collection. Illustration by the French artist Bonsomme.

Wangbone’s continued tribulations with Cathy Earnshaw (in another story, “Trapped in the Caverns of the Sorority Catacombs,” Wangbone is pressed into participating in a panty raid and discovers that the female creature that haunts the sorority’s catacombs is in fact his ex-girlfriend the Queen Berenbee, a giant queen bee that wants him back – Cathy Earnshaw walks in on them just before Wangbone has had a chance to push the queen bee off him) highlight another of EPA’s recurring themes: The difficulty in dealing with women. His female characters tend to be witches, constantly cursing the men around them; shrill, shrewlike hags who are only redeemed in (usually violent) death; or completely inaccessible, in the form of ghosts or visitors from other dimensions. Although one is reluctant to ascribe too much weight to the experiences of EPA’s life when discussing his fiction, it hardly seems improbable to suggest that some of EPA’s feminine anguish stemmed from his relationship with his mother, Norma.

Not much is known about her. She was heavy enough that her pregnancy was relatively unnoticed. Perhaps she herself did not notice it – as EPA later acknowledged in a letter to DAS,

“At that most disturbing of eras, after the fall of the South, the barest standards of feminine decorum were strictly enforced, perhaps as a manner of compensating for the attainting of the region’s ignominious defeat. An unmarried woman with a child was a scandalous nightmare provocation, a slithering and simpering monstrosity that anyone would hope to avoid like a child with oozing facial pustules, most especially someone as emotionally fragile as that thing that was my Mother.”

It was with her own mother’s help that Norma delivered EPA at home. She did not take the boy outside their home until he was four years old, and then told people she was his nephew. Apparently disappointed that she’d not had a girl, Norma nicknamed her son “Honeysuckle,” which would stick with him the rest of her life.

As problematic as were EPA’s portrayals of women, his portrayals of non-white characters were worse. This is perhaps to be expected from a writer who came of age in the deep south in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. EPA grew up around people who resented losing the war, and the fact that those men and women who had once been considered “property” were now to be, at least officially, recognized as human beings with rights. Nevertheless, EPA’s portrayals of black characters have been the subject of much debate among followers of classic pulp works. In the Wangbone stories, for example, the rivals to Upperwhere University were a group of “sooty skinned, animalistic tribesmen” called The Mults, who are often seen in the mountains that surround the campus, watching ominously with their “large, bulbous eyes lit with sickening fire,” “shaking their weapons in furious time with the rhythm of their own throbbing ictus,” and “dancing about in a maddening terpsichorean fulmination.” As suggested by these descriptions, EPA seems to have feared more than hated black people. Certainly at this point in America’s history racism was an unfortunately common occurrence and authors often used ethnic shorthand language in creating their characterizations. Modern apologists for EPA’s works have noted that the Wangbone stories take place in a fictional world called “Upperwhere,” which has little relation to reality. “Mults” are essentially an alien race, they claim. This overlooks the fact that the Upperwhere characters are based on types from all of literature, including stories based in the “real world.”

Some go even further. In the mid-1970s, as a minor resurgence of EPA popularity was dying down, a fantasy fan called P. Michael Brean took to the Winter 1974 issue of the fanzine Rocket to Almuric to defend him:

“[T]o suggest that Ervin Ashton was racist is ludicrous. The times in which he was writing plainly show us that everyone was racist back then and, besides, Ervin Ashton never actually lynched anyone, that we know of. He barely even left his house. He was never anyone’s boss and never had any authority over anyone. Moreover, he did have one Chinese character, Mi So Wong [who appeared in EPA’s story “The Sepulchre of the Dead”], who was intelligent and driven to commit his foul deeds not by any so-called ‘native evil,’ but by a bad disposition. His Indian thief, The Emerald Dacoit [who appeared in multiple EPA stories, including “From the Desert, a Dusky Death”] was a gentleman who used his wits to steal from wealthy British imperialists.”

Tellingly, while Brean’s essay spends several more paragraphs on the characters of Mi So Wong, who appeared in exactly one of EPA’s stories, and The Emerald Dacoit, who appeared in four stories (and in those, the “wealthy British imperialists” were the heroes), the character of Lazarus Abel receives only one dismissive mention.

Lazarus Abel was a preacher with supernatural powers who fought against the black magic practiced by slaves in the deep south in the early 1800s. He also searched for runaway slaves, returning them to their masters so as to “help civilize the savage ebon monsters.” In one story, Lazarus actually travels to Africa to help capture “Cimmerian skinned devils” for the purposes of selling them into slavery “to the white skinned people who would provide to them a palliative, civilizing influence.” This is a startling suggestion, even for fiction of the time – that slavery could be considered a “civilizing influence.”

The Lazarus Abel stories are difficult to read, and most of EPA’s fans choose not to (they have never been reprinted) – they provide a disturbing snapshot of an otherwise gifted writer’s worst instincts. Interestingly, all of the Lazarus Abel stories appeared in Hoary Tales, a magazine created specifically to tap into the lucrative racist fantasy market, a subgenre that thrived in the open up until the mid-1930s. Many have argued that Lazarus Abel was merely a cynical attempt to cash in on a trend, and that the stories featuring the character were strictly for money (Hoary Tales paid better than any other pulp to which EPA was able to sell); nevertheless, they are an uneasy subdivision of EPA’s oeuvre. This brief overview essay is probably not the best place to get into that part of his history.

EPA’s death was as enigmatic as his life. He seems to have simply dropped off the face of the earth in 1928. Ironically, in letters to DAS, he described being happier than he could ever remember, and had, in fact, met a woman with whom for the first time in his life he was falling in love. Given the sometimes overt sexual anxiety of his stories, and even the subliminal sexual anxiety (the idea of family curses that follow generations through copulation), it was an astonishing turn even for EPA himself, who stated in a letter to DAS,

“I cannot believe myself that I have found such a creature as this wonderful thing that has lit the darkest corners of my life. She is my most prized match now, my feminine double, and when I am not with her I am thinking of her, wondering where she might be and what she might be doing, and wishing that she would finally return to me once again.”

His descriptions of this new female companion were effusive and intriguing. What must EPA’s “feminine double” have been like? In response to an epistolary query from DAS, EPA claimed she was,

“[T]he most charming creature I have ever laid eyes upon. Her skin is soft and white, as pale as white marble, as pristine as an unsullied snow freshly fallen in a natural vista. Her hair is lustrous, luminous, her smile lights up the aether around her, and like a torch that consumes the oxygen in the air around her when I am with her I feel dizzy, lightheaded, and slightly nauseated, I am often subject to blackouts.”

Compare these touchingly effulgent declarations to a letter written seven years prior, to his fellow pulp author Alexander P. Scanlon, who wrote romantic tales under the pen-name Dame Imogene Carol Merriwether:

“The copulatory action is certainly the most vile of all human endeavors. Exchanging of those internal liquids whose proper place is to be consigned deep within the dark recesses of the human shell must certainly be the cruelest joke which fate plays upon the race. The thought of engaging in such a filthy enterprise shivers my skin.”

In May of 1928, DAS wrote three letters to EPA, none of which received a reply. A year of research, including a trip to EPA’s home, revealed that EPA had vanished. In his introduction to the Prancer Books edition of House of the 30 Day Curse, DAS describes the events which followed:

When I arrived, I was greeted by the two aunts with whom he shared the home. It was in dilapidated condition, drafty, with peeling paint and bare walls, sinking into the earth, refuse strewn about. There was an odor that permeated the walls, familiar to me somehow, but I could not place it. His aunts were both physically imposing women who left their undergarments strewn about. One of the women was wearing nothing by a flimsy set of bedclothes; the other wore an elaborate but fraying petticoated dress that might have fit her thirty years before, when it had last been in fashion.

When I asked them about their nephew the one in bedclothes (they refused to give me their names, and Ashton had only made passing reference to them in his letters) laughed phlegmily and said, ‘Maybe he killed himself!’

Startled, I asked why it was she thought that, and the other answered, ‘He probably just ran away with his little belle!’

The gist of the whole unpleasant conversation was that this magnificent writer’s aunts neither knew nor cared where he was; they were glad to be rid of him and weren’t interested in asking questions. In fact, it wasn’t until I told them that I was interested in managing Ashton’s literary estate that they showed any interest in him at all, and then only because of the potential income his writings might have provided.

No one else in Madison knew of the unnamed woman in the letters. Indeed, very few of Madison’s residents even knew that there had been a writer among them. Sadly, there was not even a photograph of the young man in the family’s home.

In spite of resistance from EPA’s aunts, DAS made it his life’s goal to preserving EPA’s works. In addition to taking possession of as many of EPA’s unpublished manuscripts and correspondence as he could carry, he collected every magazine in which EPA’s stories appeared, and spent decades creating a chronology for all of his modern, historical, and fantastical fiction. He edited and revised many of the stories that were plagued by anachronisms and inaccuracies. He took stories that had featured lesser, or one-off characters, such as the mostly forgettable Soursoom and Graggoth stories, and revised them to be part of the larger Wangbone mythos.

DAS published occasional stories and poems in fanzines and in fantasy anthologies throughout the 1950s and 1960s. The stories gained in stature slowly, but eventually started to garner attention outside of traditional fandom, attracting the attention of famous and infamous artists around the world. In an interview with the Village Voice from 1978, “El Topo” filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky claimed,

“I wanted to make 30 Day Curse as a film – I would have the door of the house a giant vagina – so wonderful! But we couldn’t get the rights! The lawyers didn’t know who had them! So I decided it would be easier to try to make a film of Frank Herbert’s ‘Dune’!”

Other filmmakers who have tried to get EPA’s properties made into films include Ken Russell, who had supposedly cast Oliver Reed in the title role of “Wangbone” (it was to be their follow up to “The Devils”), Ulli Lommel, and Stuart Gordon, who had wanted to film the story “The Perineum in the Sky” as an episode of the television series “Masters of Horror.”

EPA’s reputation as both a compelling writer and an enigmatic human being was enhanced by the publication of two collections of his works in 1970. Prancer Books, a boutique publisher of homoerotic fantasy based in San Francisco (The Butterfly Trilogy, Sticked & Stoned, The Alkahest Wand), brought out a collection of Wangbone stories, and another of “tales macabre” (and the long poem, “A Cavernous Manse, Enmusicked with Evil”). In a 1983 interview with the fanzine “Fantasy Worlds Collector,” Prancer Books publisher Mychaela (formerly Michael) Bonnera said,

“By 1970 when the books were released, there was this sort of mythology about his [EPA’s] works. People had only read bits and pieces here and there, so there was a real excitement about the books. … They were the first “head books,’ books that you were supposed to read when you were high. To be honest, I think the stories were a lot better that way. But you had people thinking, ‘Man, if I read this book my brain’s gonna explode!’”

Although the collections featured compelling covers by the renowned French comics illustrator Charles “Bonsomme” Chouinard*, the books sold poorly. Apparently there weren’t enough “heads” who were into fantasy fiction.

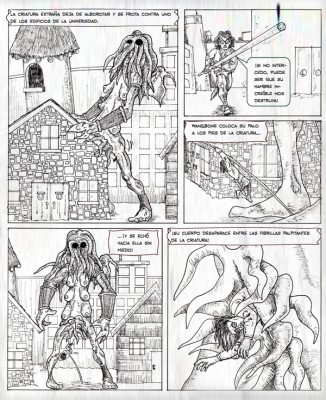

EPA’s voice was quieted once again, until 1974, when an issue of the Mexican comic magazine “Cuentos Brutos” published an adaptation of the Wangbone story “From the Ice – A Horror!”, illustrated by “Roueben Austronesia” (actually Filipino artist Fernando Luna). This story is unique in that it features what is probably the first drawing of an “Elder of Underwhere” (discounting Bonsomme’s illustration of the “House” on the cover of Prancer’s 30 Day Curse collection).

One page from an issue of the Mexican comics magazine "Cuentos Brutos," featuring an adaptation of the Wangbone story "From the Ice --A Horror!"

Curiously, this represented Luna’s last published work – did depicting an Elder of Underwhere drive him insane?

(An Elder of Underwhere would make a cameo appearance, of sorts, in another comic book – the final issue of the American graphic novel series Watchmen, in the form of the strange creature that destroys New York. Illustrator Dave Gibbons has said that EPA’s descriptions of the Elders were an influence on the design.)

The annals of literary history are littered with the forgotten remains of thousands of authors who provided hours of entertainment and escape to dozens of readers. We cannot recover them all, but there are certainly a few who merit rediscovery. Ervin Phillip Ashton, the author of more than 1,500 short stories, novelettes, novels, and poems of visionary fantasy, is just such a writer.

*An earlier version of this essay incorrectly identified French illustrator Charles “Bonsomme” Chouinard as Jean-Claude “Bonsomme” Choinaurd. I regret the error.

Partial bibliography of works cited and/or consulted:

Abrams, M.H., Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature, W. W. Norton & Co, New York, 1973

Addington, Elizabeth, “Racist Fantasy: The Rise of the Black, Yellow, Brown, and Red Menaces in Early 20th Century Pop Culture,” essay appearing in Essays in Low Culture: The Worlds Below, University of Omaha Press, Omaha, 1981

Ashton, Phillip Ervin, various correspondence (unpublished)

Ashton, Phillip Ervin, House of the 30 Day Curse, Prancer Books, San Francisco, 1970

Ashton, Phillip Ervin, Wangbone, Prancer Books, San Francisco, 1970

Bonnera, Mychaela, “He Dreamed of Wangbone,” interview appearing in “Fantasy Worlds Collector,” 1983 issue

Brean, P. Michael, “Is Wangbone a Racist?” essay appearing in Rocket to Almuric, Winter 1974 edition

Gibbons, Dave, Watching the Watchmen: The Definitive Companion to the Ultimate Graphic Novel, Titan Books, London, 2008

Gilbert, Sandra M. and Gubar, Susan, The Madwoman in the Attic, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1979

Jodorowsky, Alejandro, “Master of the Dreamscape: The World’s Most Subversive Filmmaker Speaks,” interview appearing in the Village Voice November 8, 1978 edition.

Luna, Fernando, et al, “Wangbone Y Locura,” “Cuentos Brutos,” March 1974 edition

“Masters of Horror” season 1 region 2 DVD box set, liner notes

Peters, Teri, “Heaving Breasts, But No Genitalia: Why Karton the Warrior Could Never Get the Lay of the Land,” essay appearing in They Never Did: Observations on the Sexless Age and the Reach of Victorianism in the 20th Century, Wisconsin University Press, Madison, 1992

Russett, Margaret, Fictions and Fakes, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006

Sprague, D. August, introduction to House of the 30 Day Curse, Prancer Books, San Francisco, 1970

Sprague, D. August, “He Was a Dreamer, by God: The Ervin Phillip Ashton Story, as Much as is Known,” essay appearing in Mystery Worlds of Amazing Fiction, August 1966 edition

Sprague, D. August, various essays and correspondence (unpublished)

Warner, Marina, Phantasmagoria, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006

Various issues of Fantastic Oddities, Eerie Tales, Eerie Worlds, Hoary Tales, FantastiFiction, Tales of Fear, The Eerie Nightmares, Strange Times, et al.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Discussion Area - Leave a Comment