The Toy Story trilogy: Getting emotional about corporate anxiety

Last weekend, the pay cable channel Starz ran the three “Toy Story” films back-to-back. Watching them one after the other provided roughly the same experience as when you’re forced to sit through an hours-long corporate meeting at which a compelling, entertaining, but ultimately hollow speaker hectors you about how much more you could be doing to help the corporation succeed. And then telling you that, for your efforts, you should expect nothing more than the personal satisfaction of knowing you’d helped the CEO make an extra $20 million. Oh, and you’re supposed to find the entire proceeding poignant.

The “Toy Story” trilogy is a perfect encapsulation of anxiety in the post-modern world. Corporate anxiety. The films promote groupthink, and the acceptance of the purveyors of mass entertainment and consumables as benevolent entities never to be questioned. In a world in which new technology is giving consumers more control over how they consume their entertainment, the big corporations want you to remember who it was who gave you your Woody.

In the first “Toy Story” film, we’re introduced to the characters and the concept. Your toys come to life when you’re not around. The assembly-line produced hunks of plastic and fabric that were created by the thousands in factories are not simply tools of promotion – they are in fact sentient beings, imbued with personalities by the artisans who created them to make money for the corporations for which they work.

In other words, the entertainment conglomerates give life.

And we all have a responsibility to that life. The consumers who purchase the toys that were created as marketing devices to make money are to use those marketing tools in the manner in which the artisans and corporate executives intended.

The toys themselves have some awareness of their place in the world. Early in the film, Woody lays out the lot of the sentient toy: “It doesn’t matter how much we’re played with… What matters is that we’re here for Andy when he needs us; that’s what we’re made for, right?” This mantra is repeated throughout the series in one way or another, enough that its importance is clear. Accept your lot unquestioningly. What remains in doubt is exactly to whom Woody’s loyalties truly lie – that will not be made clear until the end of the third film.

The neurotic toys to which you, as an “owner” owe so much responsibility, worry over Andy’s birthday party. In particular, will he receive as a gift a new toy that will send one of the old toys to the next garage sale? As it turns out, Andy gets a Buzz Lightyear, and when he is introduced to the other toys, the following exchange occurs:

Hamm: Where are you from? Singapore? Hong Kong?

Mr. Potato Head: I’m from Playskool.

Rex: I’m from Mattel… I’m actually from a smaller company that was purchased by Mattel in a leveraged buyout.

The film is making an overt reference to the mass produced nature of these products for which we’re supposed to have a rooting emotional interest. Factory made hunks of plastic, as Lotso will say in the third film. Moreover, they are created by corporations that purchase other, smaller companies in “leveraged buyouts” — the corporation gets even bigger by swallowing up a smaller company. As we’ll see as the trilogy moves along, there is no subtext to these films – they are an overt paean to the influence of large corporations on our lives. (And, as it turns out, late in the first film we learn that Buzz was “Made in Taiwan.”)

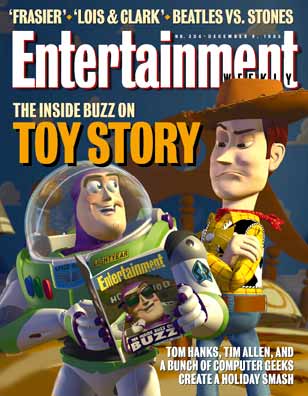

“Toy Story” also features a touching allegory about the ways in which corporations can cooperate with each other to influence consumers. When Woody and Buzz first meet, Woody is jealous that Andy might favor Buzz over him, and admonishes Buzz, “You stay away from Andy. He’s mine, and no one is taking him away from me.” Over the course of the film, Woody and Buzz come to realize that there’s room in Andy’s life for more than one corporate source of influence. After all, Entertainment Weekly is owned by Time-Warner, but that doesn’t mean that a Disney/Pixar production like “Toy Story” can’t be featured on the cover.

Time Warner owned Entertainment Weekly placed Disney/Pixar's Toy Story on its cover. If corporations can cooperate, why can't individuals? It would be a better world if we learned from them.

If the two corporate products can learn to peacefully coexist, and help each other in influencing Andy’s life, then certainly children can be trained to use toys properly. When we first meet the ostensible villain, Sid, he has strapped a firecracker to the back of a toy soldier – there’s probably something to be said here about the military/industrial complex but I’m not going to say it here – and the other toys point him out to Buzz. Looking through the toy binoculars, Buzz sees Sid and asks, “You mean that happy child?” To which Mr. Potato Head replies, “That ain’t no happy child!” and Rex adds, “He tortures toys… Just for fun,” in a whiny Wallace Shawn voice.

Sid is mentally unstable. He’s not “happy.” He can’t be. Because he “tortures” toys. He takes the mass-produced hunks of plastic manufactured for licensing and merchandizing purposes and uses them in creative ways – ways the manufacturer never intended. He is the “owner,” and as such, he asserts his rights of ownership over the property he (or his parents) bought and paid for. He plays his own version of the game “Operation,” in which he takes the head from one toy and places it on the body of another. He puts one in a waffle iron. In his room he has a lava lamp in which you can see floating doll parts. Sid shows genuine creativity and ingenuity. Yet not even Sid’s noblest efforts at desecrating these tools of commerce can fully obliterate the spark of the corporation within his remixed toys – they still help Woody to “rescue” Buzz, and then, nonsensically, the toys reveal themselves to Sid, speaking directly to him, and threatening him with harm, terrifying him into taking “good care” of his toys. “We can see everything,” Woody says, menacingly. “So play nice.”

By “play nice,” Woody means, “The way the manufacturer intended.” Let’s leave aside for a minute the absurdity of the toys revealing themselves to someone (although the logistical problems of these films are difficult to overcome – at one point, Woody calls out to Sid’s sister, Hannah, to get her to leave the room. If she can hear his voice when he calls to her, why doesn’t the whole neighborhood hear Woody when he calls out through the window to the other toys in Andy’s house? For that matter, is there video surveillance at Al’s Toy Barn in the second film, or the Sunnyside Daycare Center in the third? What about traffic cameras on the streets – in the second film, wouldn’t it be suspicious to see those cones crossing the street like that?). Remember, it’s Woody who said, “It doesn’t matter how much we’re played with… What matters is that we’re here for Andy when he needs us; that’s what we’re made for, right?”

Throughout the series, Woody will insist that toys are to accept unquestioningly the decisions of their “owners.” Andy is referred to as Woody’s and Buzz’s “owner,” which only multiplies the menacing aspects of these films. The toys after all are sentient beings, and the casual acceptance that such creatures can have owners is striking. The full impact of this idea is again saved for the third film. For now, we get only a hint of the full message of the trilogy in the fact that Woody fights against Sid’s treatment of his own toys. There is something deeper going on – it’s not the “owners” who are actually in control.

The second “Toy Story” film, “Toy Story 2,” takes on the collector’s market. The alleged villain of that film, Al, is the owner of the toy store Al’s Toy Barn and a collector who keeps his toys in pristine condition in their original packaging (“Mint in the box,” as Jessie says, in reference to Stinky Pete the Prospector). The value of these toys increases, and Al is able to sell the toys for much more than he paid the corporation that made the toy. Al is making a profit, while Big Toy is left with only the original sale price. As if that subtext might be too subtle for the viewer – Al is essentially stealing from the corporation that originally made the toy – Al is shown literally stealing the Woody doll from Andy’s mother’s garage sale, when she refuses to sell him the toy. For his part, Woody is only at the garage sale to retrieve Wheezy, the broken penguin-shaped squeak toy that Andy had long since forgotten. For some reason, Andy’s mother locks Woody into the money box and then leaves that box unattended, with the venal Al standing right there, having just anxiously offered her fifty bucks for it.

Al’s effort to sell a complete set of Woody-related merchandising, including piggy banks, record players, lunchboxes, and cardboard cut-out advertising, to a museum in Japan, is derided (globalism is fine when the toys are “made in Taiwan,” but when the corporations aren’t directly benefiting, it is wrong). He has assembled his collection with care, but he has done so with a profit motive that cuts out the corporation that created Woody. Woody, who was apparently unaware of the full origins of his manufacture, is overwhelmed seeing all of these other items bearing his likeness. (Why doesn’t the Woody yo-yo come to life? Or the Woody piggy bank?) What Woody discovers is that he is a toy advertisement for a long-forgotten marionette television program. In other words, Woody is a cog in a very big machine meant to produce money for the parties involved in the creation of the original television program. He is simply another employee – a lesson he won’t fully come to learn until the end of the third film. In the meantime, when Buzz and the other toys finally make it back to Al’s apartment (menacingly, the building has a sign on the door reading “NO CHILDREN ALLOWED” – again, in case the audience was too dense to pick up on the fact that Al just ain’t right) and Woody tells him he wants to go to Japan to be part of a toy museum exhibit of the complete Woody merchandising set (and by the way, anyone who’s ever seen either of the “Night at the Museum” films knows how much fun those places can be for inanimate objects), Buzz lays on the guilt and smokescreens the audience by telling him that it was Woody who taught him that “Life’s only worth living if you’re being loved by a kid.”

That is true. Earning money for the manufacturer is the toys’ entire raison d’être. And if the kids don’t love their toys, their parents won’t spend any money on them.

It’s telling that during the final elevator sequence, when the second Buzz Lightyear is fighting against Zurg, that there is an overt reference to the film “The Empire Strikes Back,” in which it’s revealed that Zurg is in fact Buzz’s father. The “Star Wars” films were among the first “summer blockbusters,” and they owe much of their legacy and reputation to the savvy ways in which they were licensed and marketed. Growing up, I didn’t know anyone that didn’t have at least a few “Star Wars” toys, lunchboxes, T-shirts, comic books, etc. I had them myself, and I disliked immensely the films that inspired them.

In the final “Toy Story” film, “Toy Story 3,” the corporate artisans give the audience the approved manner of consumption of their product. Andy, now preparing to go to college, plans on taking Woody with him – the instrument of childhood control making the journey to an institution of “higher learning” – while leaving the other toys in the attic. However, the toys end up at the Sunnyside Daycare center, to be the playthings of new children who do not play with the toys in the approved manner. After their first round with these children, Mr. Potato Head states, “These toddlers, they don’t know how to play with us.” It’s a daycare center of Sids, who use the toys to paint, and to pound wooden pegs. They deconstruct the toys. They are disrespectful of their intended purpose. When Woody attempts to get the others to return to Andy’s house, where they will be sent to the attic, he tells them, “If he wants us at college, or in the attic, it’s our job to be there.” Once again, Woody insists that the toys accept their job. And when the toys argue that they want to remain at the daycare center, where they will be played with in the unapproved manner, he hectors, “I can’t believe how selfish you all are.”

The toys are employees, meant to do the bidding of their boss unquestioningly. Woody’s mistake at this point is in assuming that his boss is Andy. But he isn’t their boss, and at the end of the picture, in bit that we’re meant to find “touching,” Woody comes to realize that Andy was never really his “owner.” If Andy had been an owner, like Sid, he could have done whatever he wanted with his “property.” But Andy was as much a tool as Woody. All along, Woody was working for the corporation that manufactured him. Having come to this realization that was three films in the making, Woody uses a sharpie to write a note on the box of toys intended to go into the attic (again I have a difficult time with the internal logic of these films, or lack thereof – why can the toys write notes? Why can they IM with other toys? ) to influence Andy into gifting his toys to Bonnie, the little girl who is “respectful” of the toys. But, just to be certain that Bonnie will use the toys in the manner in which they were intended, Andy introduces them to her, giving her their backstories. Like the fanboys who take to the message boards to chastise anyone who disagrees with them, and to mercilessly pontificate on some area of continuity minutiae, Andy is using brand loyalty to help indoctrinate a new generation into the corporate mindset. “Now, you gotta promise to take good care of these guys. They mean a lot to me,” he tells her.

Play with the toys until you grow up, and join the world perpetuated by the corporations that provided you with the toys in the first place – the world in which you accept unquestioningly the rules of your corporate bosses. To question them is to be “selfish.” But when you do outgrow your toys, turn them over to another child. The system perpetuates itself, with the willing participation of the consumers, who act as corporate emissaries, part of the propaganda machine, indoctrinating others into the consumption society.

Only the villain, Lotso Hugs Bear, understands the true nature of toys. “No owners mean no heartache,” he tells the toys when they first arrive at the daycare center. “We own ourselves. We control our own destiny.” That sounds like a positive message to be telling kids. But Lotso Hugs, who claims that the sentient beings “own” themselves is portrayed as a dictator, who cruelly forces the toys to, um, act like toys. Meant to be played with. Woody, with his “do what your owners say” message, is the hero.

Just before he falls into the dumpster Lotso asks Woody, “You think you’re special, cowboy? You’re a piece of plastic.” Here he has articulated the true nature of toys. That is literally what toys are. They are given meaning, and attain emotional resonance based on the advertising behind them, and how we as consumers are affected by that advertising. They are ultimately unnecessary, disposable items, but in the “Toy Story” films we, the consumers, are meant to see that we have an obligation to them — and, by extension, the corporations that created them in factories in Singapore, and that increased their size by acquiring other, smaller companies in leveraged buyouts. In Lotso’s very next sentence, he betrays his movie villainy: “You were made to be thrown away.” Oh, no, he was not. Toys most definitely are not made to be thrown away. They are made to make money for the corporations that designed and manufactured them. That is the most important thing. Only a desperate, dastardly villain would imply that a merchandizing vessel was disposable.

The nearly-universal critical acclaim for these films is evidence of the corporate groupthink that they celebrate. Film critics are part of the major studio promotion machine, from their work for corporate-owned magazines, to their “critic’s circle awards” that are used in corporate marketing. Blurbs are used on movie posters, and in commercials. “See the film that received two middle fingers up from Ebert and Etc!”

And when two film critics dared to express contrary ideas about the third “Toy Story” film, and in the process “ruined” the trilogy’s perfect 100% Tomatometer score, it was the RottenTomatoBots who came out in force to provide free protection for the major-studio megabudgeted, heavily-merchandized films. Even the director of “Toy Story 3,” Lee Unkrich, got in on the act, taking to twitter to offer his pity to those who didn’t like his film:

“You are sad, strange little men, and you have my pity.”

The release years of the “Toy Story” films have been a time of great and rapid change for the entertainment industry. Some have argued that the purveyors of popular entertainment have not responded well to these changes. In 1995, the year of release of the first “Toy Story” film, the DVD was introduced to the world. It was the rise of the DVD that instigated a change in the way in which movie studios packaged their products for home use. Where they had been following a rental business model, which had greatly benefited other entities like Blockbuster and Hollywood Video, they now moved to a primarily sales-driven business model. The price points of the DVDs decreased, while the number of “special features” on the discs increased, thanks to the increased amount of information the discs could hold. This meant higher individual sales and more money for the studios. They cut out the middle men, and now — when was the last time you saw a Hollywood Video?

DVDs had another bonus, besides their higher picture quality and the increased number of features that came with the discs. They had technology that made copying them difficult. They could also be released by “regions,” controlling the location in which a movie could be viewed.

More troubling to the studios was the rise of the internet. It was during the early 1990s that the general public began to learn more about the internet, which was growing beyond its largely academic origins. By 1999, when the second “Toy Story” film was released, 40 % of the US population over the age of 16 have access to the internet. As technology increased and became more widely-accessible, consumers have become more empowered in how they use and process their entertainment. Popular culture is dominated by large corporate interests that have a large financial stake in insuring that you consume their products in the manner in which they want. Their reactions to declining movie ticket sales have been telling. They have offered reboots, remakes, and sequels. They have offered 3-D, with its elevated ticket prices and glasses (they’re telling you to put something on your face when you attend one of these films!).

Still, the studios are losing control of their audience. Theater attendance is down, while services like Netflix and Redbox are increasing. For $7.99 per month, a person can get access to a complete library of films online. For $1.00 a night a person can go to a kiosk and rent a DVD. Naturally, the corporations that produce the entertainment don’t like this, and have been fighting to control Netflix and Redbox. Studios have also begun the process of offering movies on pay-per-view 60 days after their initial theatrical release.

These corporations aren’t content to merely influence us through our entertainment, and to promote brand loyalty by providing us with products we enjoy using or think we need. They actively try to limit our choices, often using the government itself to do it. In 2007, several toys were recalled because of a scare over the presence of lead and other chemicals. In 2008, Congress drafted a drastic and alarmist bill called the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act, goaded by “consumer advocates” and “environmental groups” looking to regulate products aimed at anyone 12 and under.

Rather than fight the law, or push for something more sensible and realistic, Mattel (which manufactured six of the toys that were recalled — and, the company that bought in a “leveraged buyout” the smaller company that produced Rex) spent more than $1 million lobbying congress for a provision that would directly benefit them:

Turns out, when Mattel got lemons, it decided to make lead-tainted lemonade (leadonade?). As luck would have it, Mattel already operates several of its own toy testing labs, including those in Mexico, China, Malaysia, Indonesia and California.

So while most small toymakers had no idea this law was coming down the pike until it was too late, Mattel spent $1 million lobbying for a little provision to be included in the CPSIA permitting companies to test their own toys in “firewalled” labs that have won Consumer Product Safety Commission approval.

The million bucks was well spent, as Mattel gained approval late last week to test its own toys in the sites listed above—just as the window for delayed enforcement closed.

Instead of winding up hurting, Mattel now has a cost advantage on mandatory testing, and a handy new government-sponsored barrier to entry for its competitors.

Thanks to this law, it’s the big corporations that will have an even greater stranglehold on the market for children’s toys. Small manufacturers are fighting the law, but given the fact that it passed congress with only one dissenting vote, it seems unlikely the law will be changed. After all, Mattel will benefit greatly. So will Walmart and Target. It’s second hand and thrift stores and the lower-income people who use them that will suffer, but then again, we need people to buy NEW ITEMS, to help stimulate the economy.

Interestingly, the Motion Picture Association of America just hired disgraced former senator Christopher Dodd as its chief. This is the same MPAA that has fought hard to ensure that you do not have access to technology that would allow you to copy for your own use DVDs that you have purchased yourself.

Even after we have purchased a product, the company that sold it to us wants you to know it really still belongs to them. Oh, but they tell us that people will use this technology to pirate videos. Piracy, we have been told, is the same as taking money from the just-plain-folks stuntmen and set painters who work hard every day to entertain you in big-budget films that cost $15 to see in a theater. And speaking of piracy, the government has without warning been seizing the domains of people who have been accused of video piracy, but not convicted.

Corporations have been using copyright law to go after people who create their own versions of movie trailers, or who remix scenes from films. In February 2010, the New York Times posted an article explaining how you can make your own remix of a scene from the film “Downfall.” You might remember that those were popular for awhile – Adolph Hitler, down in his bunker, passionately ranting about, oh Sarah Palin resigning as governor of Alaska, or that Oasis split up.

In April of 2010, YouTube removed the parodies at the request of the copyright holder, Constantin films.

The “Toy Story” films, in particular the second, are magnificently entertaining. They have a lot of humor, action, and wit. They are very well constructed. Some of the sequences are among the best ever put to film. (I particularly like the sequence in which Buzz Lightyear et al use orange traffic cones to cross the highway to get to Al’s Toy Barn in the second film. That scene is a perfect mixture of comedy and action, almost as good as anything Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton ever did.) But their quality level is part of what makes them so insidious. Propaganda doesn’t work if it’s not entertaining. Much of their charm comes from our shared experience growing up in a culture that elevates consumption, and the desire to possess … things. As children, it is toys. As adults, it’s a different type of toy – an iPad, for instance. Or a smart phone. And we must update our facebook page and twitter feed to ensure that everyone knows we just got the latest version.

Film is a product. It is commerce. Now more than ever. As A.Jaye put it, over at the blog Thrill Fiction,

Film is the bastard cousin of the arts of storytelling because it alone is created primarily as a source of commerce. The art in film is despite the motion picture industry not because of it.

The “Toy Story” films are artful. If they were poorly constructed, they would be discarded; we’d all be Sids, firecrackering the first film, and killing the franchise. But, like Bonnie of “Toy Story 3,” the creators of the “Toy Story” films grew up with corporate-approved entertainment. They learned the lessons of what worked from Hanna Barbera’s, Ruby Spears’ and Filmation‘s efforts at commercial entertainment and applied them accordingly. For the adults who grew up in the system, these films are moving and poignant. They’re meant to appeal to that part of us that becomes emotional playing Chutes & Ladders.

This is the life you’ve made for yourself, America. It’s the world you’ve given to your children; a world in which we feel emotional about our things. One of the alleged “film critics” at Entertainment Weekly, Owen Gleiberman, wrote a simpering post in which he opened up about how the third “Toy Story”‘ film was so emotional for him that it actually made him cry. He should have been embarrassed about falling so completely for the manipulation, but he was proud. In an unintentionally hilarious explanation as to why the ending of the film made him so emotional, he completely misses or ignores the subtext of the films — the most overt subtext in the history of subtexts:

The thing about the end of Toy Story 3 is that it works on so many layers. It doesn’t so much push buttons as touch little themes and bubbles of emotion that have been planted throughout the movie. On the simplest level, of course, the ending is a homecoming, with Woody, Buzz, and the rest of the gang finally finding a place for themselves — finding, that is, a child, a little girl named Bonnie (voiced by Emily Hahn), to be their newly devoted owner and playmaster and friend. It’s a classic happy finale: They’ve been rescued from the darkness and given a home. That’s enough to give you that Lassie Come Home three-hankie feeling right there. Andy’s introduction of each of the toys to Bonnie, as he moves on to adulthood, is a series of little heart tugs: nostalgia and loss and friendship and and rebirth, all at the same time.

As always, the desire and goal of the film’s chattering menagerie of toy pals is, quite simply, to be played with, and that in itself is such a highly delicate and unusual and touching force to encounter in the heroes of a kids’ movie. It’s just so…generous. (They’re like faithful, eager-to-play pups who come with their own toy-size, squabbling, play-act version of the egos of humans.) It’s what’s always been so moving about the Toy Story toys: that they’re programmed, in their plastic and polyster DNA, to be part of something larger than themselves — to do everything in their power to make a kid glow with delight. When Woody decides to stay with the gang, rather than go off to college with Andy, he’s affirming his very destiny as a plaything. He has to abandon the owner whose favorite toy he was to be the true toy he is.

He wasn’t alone — remember that even the director of the film said that people who didn’t appreciate it completely were “sad, strange little men” worthy of “pity.” You see, if you do not respond to the product in the way in which the corporate artisans intended, there is something wrong with you. Like Sid, you just can’t be happy if you don’t play with “your” toys in the acceptable way. It’s not entirely Mr. Gleiberman’s fault — the toys of “Toy Story” are more interesting, and more expressive, than the humans who “own” them. It helps that the animated toys look more realistic and sympathetic in an uncanny-valley sort of way than the human creatures that occasionally populate the film. It also helps that the humans of the film are merely cyphers, whose existence is meaningful only when they are interacting with their toys.

The entertainment conglomerates give life, and they make it meaningful. Please do not question them.

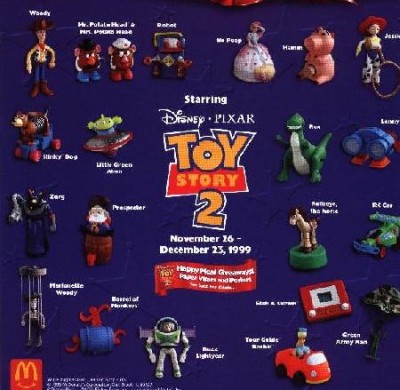

This is why the Toy Story films were made. So the characters could be licensed as Happy Meal toys. Oh, and to make film "critics" cry from emotion.

Latest posts by Ricky Sprague (Posts)

- Meet the start-ups that are thriving in the current economic recovery - May 27, 2016

- How a Wonder Woman comic from 1942 led to the Great California Cow Exodus of 2012, maybe - November 28, 2012

- A common-sense approach to restoring economic prosperity - November 19, 2012

- New Philip K. Dick novel too absurd to be believed - September 17, 2012

- My 90 Days, 90 Reasons submission - September 12, 2012

Print This Post

Print This Post

Thanks for a most instructive commentary.