First, the story, then the story behind the story.

The Stacker

by Scott Stein

The stack was developing as a sort of snowflake, with a symmetry as unconventional as it was unconditional. The columns at the snowflake’s outer tips consisted of the rectangular crates, which grew larger as they neared the ceiling, and the crates with still more sides also grew progressively larger throughout the stack. The stack was sorted by code in a diagonal pattern, both alphabetically and numerically, and a chessboard arrangement had also emerged, with the alternation of light and dark wood crates throughout.

Had the Stacker intended all of it? Any of it? He didn’t understand how it had worked out to such perfection. The pieces had just fallen into place. He couldn’t believe the beauty he had brought into the world, and stood for a moment, still and silent and wondering how it had all happened. Finally, he had a stack that he wanted people to see, that people were capable of seeing. The other stackers would never tell him they liked it, he knew that. They would resent his accomplishment; their blind jealousy wouldn’t allow them to acknowledge the greatness of his art. He didn’t need them anyway. A stack as important as this one could not be long ignored.

With a synthesized chime and a flashing red light, the freight elevator’s doors parted. For a full minute, the automated treadmill churned loudly as it steadily spewed more crates into the room. The Stacker laughed for a second. This was clearly a joke. There was never more than one delivery per day. Someone was having fun at his expense. Who could be playing games like this? No one. It was no joke. He had no friends, no one who would trouble with such childishness. And tampering with crates was a serious offense. No, this was a real shipment, and he would have to assimilate it into the rest of the stack. How could they do this to him? He looked at the perfection of the stack he had constructed, marveled at its purity, and was afraid to disturb it, to introduce new crates that might upset the harmony it embodied.

But looking upon it made him know that he had nothing to fear. He was now one of the Masters. The finest stack in history stood before him, fashioned by his own hands, and this new challenge could only result in further greatness. He strapped a crate and maneuvered it into position, and another, and another. The stack reached nearly to the ceiling. He worked even more frantically than he had the first time, and the stack grew in size and beauty. The symmetry continued, and the top half of the stack mirrored the lower, with the new crates now getting smaller as they approached more glorious heights. Certainly it would be the subject of numerous papers and articles. Probably the University would offer research grants to study it at length. The Stacker was sure to be made a supervisor. He would likely tour the country, speak to panels, and help with important decisions and policies.

He swung and hooked and strapped until his hands burned and his back ached. He ran and leapt and nearly danced as he became one with the stack, until he understood each crate as if he had built it himself, until his clothes were wet and his arms were heavy. Then, still sweating and panting, he realized that it was done. The stack was complete. Its giant shadow drowned out the light, and he stood, shivering in awe. He wished it weren’t so dark. He couldn’t get a good look at the stack, and turned toward the wall to brighten the light, but bumped into a crate instead. He was inside the stack, in the center of the immense snowflake, which was everywhere flush with the ceiling. The Stacker had walled himself in. He couldn’t get out and couldn’t see the stack from the outside, as it was meant to be seen. He had to find a way out. The collators would be by soon, there would be transfer requests, and he couldn’t be found in this ridiculous position, trapped by his own creation. The greatness of his stack would be lost if it got out that he had imprisoned himself. The first thing one learned as a stacker was to leave a way out. The fundamentals had eluded him.

Just then there was a knocking from the hall. He didn’t answer. A banging. He held his breath and was motionless. More banging, and the Stacker heard a sheet of paper being slipped under the door and then withdrawing footfalls. He was saved. He had bolted the door, and no one would be able to enter until he unlocked it himself.

The Stacker grabbed a crate and slowly began shimmying it loose. He had designed the stack so that he could remove crates when called upon without disturbing the integrity of the overall structure. True, he had intended to remove them only from the outside (after he’d shown the stack to the proper persons and had it photographed), but that shouldn’t make any difference. He slid the crate from side to side before finally pulling it through.

There was a distant creak and a rumble, and the giant shadow wavered. The columns swayed slightly, and the Stacker ran to one and tried to hold it in place. There was a perfectly square hole where he’d pulled the crate loose, large enough for him to escape from the deteriorating stack, but he made no move toward it. He ran from one column to another, but the rumble grew louder and the wavering more severe. As the crates toppled from their height, he made no effort to evade them but struggled to brace the stack, still pitifully leaning into a trembling column when the first crate came down on his head. The entire stack followed. A deafening crash of wood sprayed throughout the room as the Stacker was crushed to death and buried beneath tons of plain, ordinary crates. On the floor next to the steel door, half-covered with dust and shards of wood, was a sheet of paper. It read: Crates sent in error. Do not stack.

—-

The story behind the story:

I wrote “The Stacker” when I was 23. It’s the first real story I ever wrote. (It’s also the first story I had accepted for publication, though not the first to be published, but I’ll talk about that later.) I’d written other stuff as an undergraduate at the University of Miami, where I majored in creative writing, but nothing I would call a story. As an undergrad fiction writer, mainly I flopped around, like a fish on a boat.

After I graduated I took a job with a small advertising agency in New York City. I answered phones when I started there, but pretty soon was writing copy for ads and brochures for toys and dog toys and wine — including Louis Jadot and Taittinger champagne.

I was going to New York University at night, after writing the dog toy copy all day. In my final term at NYU, I was working on my master’s thesis on Kafka’s short stories. For a couple of months I think I thought I was Kafka [1].

That same semester I decided to apply for MFA programs. I hadn’t written a word of fiction since getting my BA, nearly two years earlier. But MFA applications required creative writing samples. Besides, if I was going to be a fiction writer, at some point it figured that I’d have to write some fiction.

I wrote “The Stacker” over a couple of nights. With some distance now from its creation, I see three influences on this story.

One was my job, where I didn’t love what I was doing, but where I worked with people who did, who, viewed through my generic idealism at the time, took dog toys, and writing about dog toys, and photographing dog toys, a bit too seriously. The angry, perpetually hungover graphic designer I worked for talked about his work — which wasn’t particularly impressive — the way writers and artists talk about their craft. I was thinking about what art is and how people delude themselves about the importance of what they’re doing.

One was Kafka.

One were the questions I had about my own skill as a writer, the value of what I was doing, why I was doing it, whether I was fooling myself — you know, little things, like the meaning of life.

After I wrote “The Stacker,” I felt pretty good about it and for the first time chose to submit a story to literary journals. I was totally naïve about the whole process, did all the wrong things — I sent it out blind, without having read any of the journals I was submitting it to. I didn’t read literary journals. I just looked through a guidebook and picked the most prestigious literary journals I could find that allowed simultaneous submissions.

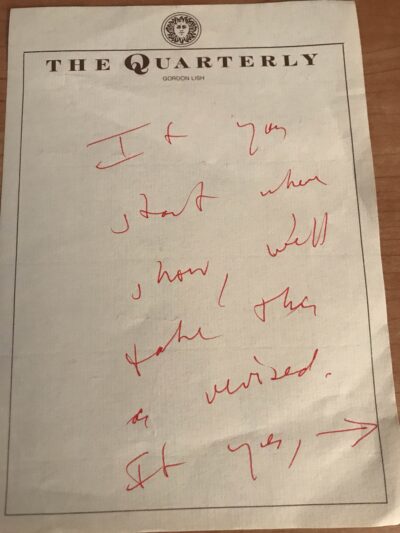

A couple of months later I got a letter from The Quarterly. Inside was my ten-page manuscript. The first six pages had giant X’s covering the entire pages. On the seventh page it said, “Start here.”

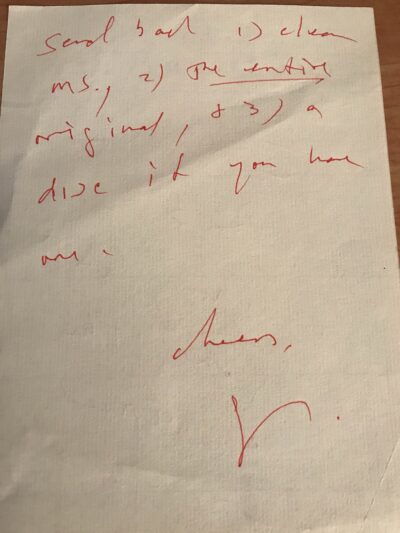

There was a handwritten note clipped to the manuscript. The handwriting (see below) might be hard to read, but it says something like, If you start where shown, we’ll take this…

It was from Gordon Lish.

At the time, I didn’t know who Gordon Lish [2] was. I didn’t know that he’d been the fiction editor at Esquire. I didn’t know that some people thought he deserved as much credit as Carver for Raymond Carver’s early stories. I didn’t know that The Quarterly was a big deal.

Anyway, I cut the first six pages and awaited my first publication, in a national literary journal edited by Gordon Lish. When I started at the MFA program at Miami, a fellow student who had heard that I had a story coming out in an upcoming issue of The Quarterly told me he’d push his own grandmother down a flight of stairs to get published there (which he stole from someone, Faulkner maybe?). I think he was joking. But it was apparent that this publication was a big deal.

Soon enough I saw the galleys, my name in print for the first time. I was to be in the next issue. It was a magical day. Then I waited. And waited. And waited some more. Weeks turned to months. Finally a letter came, explaining that The Quarterly had run out of money. The issue might have been printed already, if I remember correctly, but there was no money left to distribute the copies. The Quarterly went out of business.

I mourned for a day, then out the story went, this time with a cover letter explaining that Gordon Lish had edited it, and within a couple of weeks The G.W. Review accepted it, and “The Stacker” was finally published, about two years after I first wrote it. It turned out to be the second story I published even though it was the first I’d had accepted for publication.

The most important thing is what I learned from my one encounter with Gordon Lish, when he cut 60% of my story. It was a great lesson. I think it’s saved me 60% of the work of being a fiction writer. Ever since then I cut out 60% of the story before I start writing it.

“The Stacker” was originally published in The G.W. Review.

- Author Bio [5]

- Latest Posts [6]

Scott Stein [9]

Latest posts by Scott Stein (Posts [14])

- A Brush with Techno-Corporate-Bureaucracy [15] - May 6, 2023

- Franz Kafka’s Content Warnings [16] - June 29, 2021

- Coronavirus wisdom from great philosophers [17] - March 31, 2020

- My new novel has a publisher [18] - April 11, 2019

- Superman lacks super understanding of economics, causes of crime [19] - January 17, 2012